When I was four years old, I dismantled my sister’s talking doll—the one with the uncanny blinking eyes making eerie sounds. I remember the moment with perfect clarity: the weight of the thick brown plastic, the resistance of the head as I pried it off, the sudden reveal of red and blue wires inside her body. I wasn’t driven by cruelty or boredom. I wanted to understand what made the doll speak, laugh, and move.

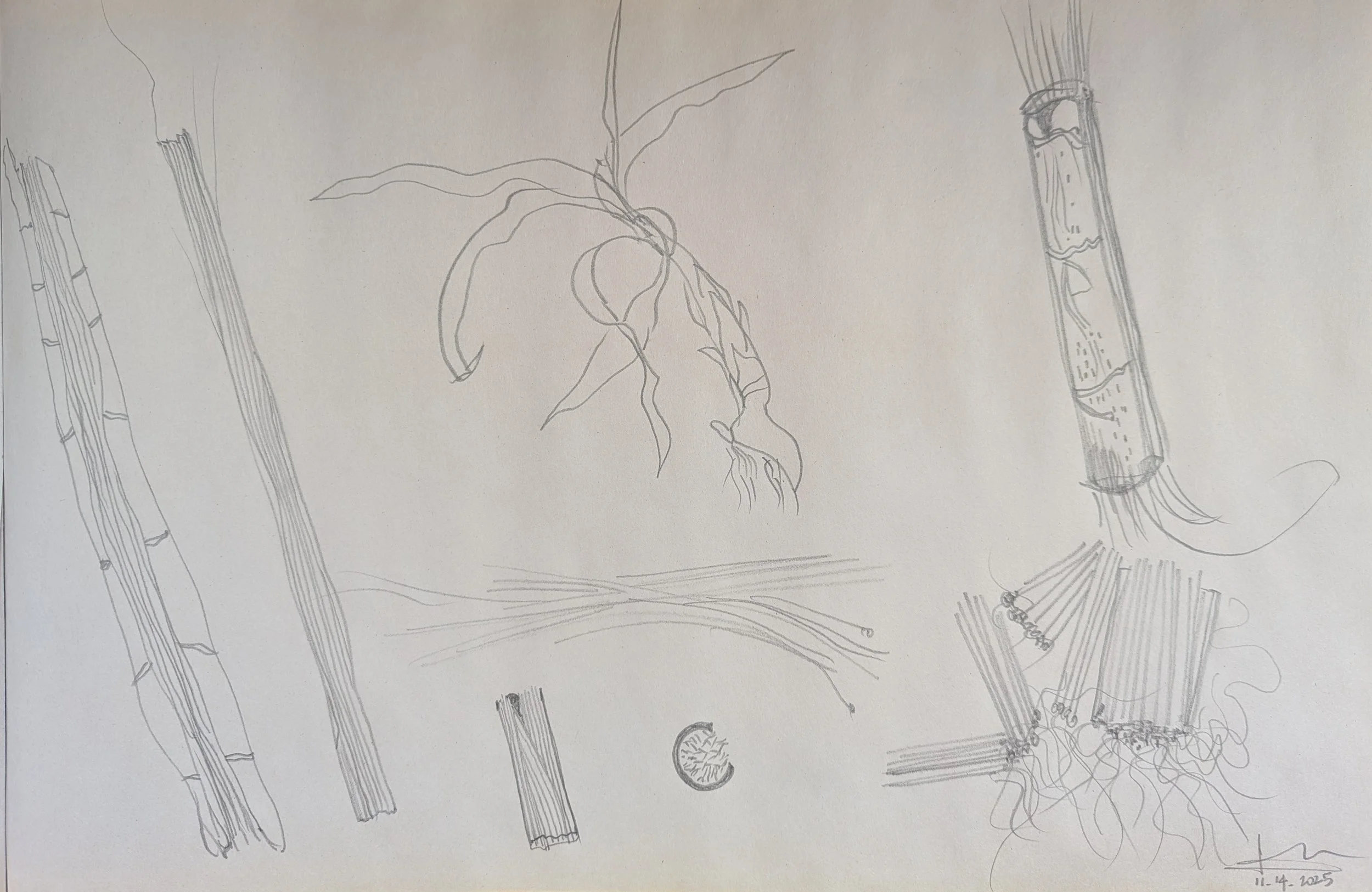

Today, more than forty years later, I felt that same hunch when reaching for pencil and paper to draw the lucky bamboo that was on its way to the garbage. I sketched its form carefully, but something in me hesitated before letting it go. Instead, I took a knife and began to cut.

pencil on paper

There is something tender in the act of dissection—an intimacy closer to listening than to breaking. When the knife slid through the cane, I expected resistance, but the interior was soft, almost spongy. The cross-sections revealed pale fibers where I thought there would be a void. I traced them with my finger, thinking of how plants record time differently from us—not in birthdays, but in layers of water and light.

Cutting the lucky bamboo, I realized that its simplicity is deceptive. Inside, it is a network of fibers—xylem and phloem arranged in bundles, a vascular chaos. These bundles look like small eyes staring back at me, or tiny cables. I remembered the doll, the red and blue wires packed tightly like veins. It felt like coming full circle with my own history: the child tearing apart a machine, the adult opening a plant with the same curiosity.

Dissection is another form of learning to see.

I thought again of Villoldo’s idea of symbiosis—how plants and humans co-produce breath. But today the collaboration felt more material. By cutting into the plant, I interrupted its metabolism, yet at the same time, I entered more deeply into its logic. I watched the severed surfaces begin to darken as air met their inner tissues. Perhaps this is why I could not simply throw it away. Something in that moment asked me to pay attention.

As I looked at the opened stems, I thought of Haraway’s call to stay with the trouble. To remain with the messy, entangled reality of things—not just their outward beauty or symbolic meaning, but the material truth of their structure, their failures, their endings, their death. The dissected lucky bamboo is no longer a symbolic object of prosperity at home. It is matter rearranged: a plant whose architecture I can now read from the inside out.

Today I realize that dissection became another form of care—an act of attention, a way of honoring its interiority.

pencil on paper

I drew each piece again—not the intact plant this time, but its anatomy. The vascular bundles, the fibrous centers, the outer rings. Where the first drawing traced its gesture, this second drawing tries to understand it. To understand me. Perhaps this is what I have always done: open things to understand how they hold life. The doll in 1984, the bamboo in 2025. My own practice—collecting soil, extracting microbial DNA, slicing sediment, revealing layers of time. A life of wanting to see how things function: the hidden negotiations that make something stand, breathe, persist.