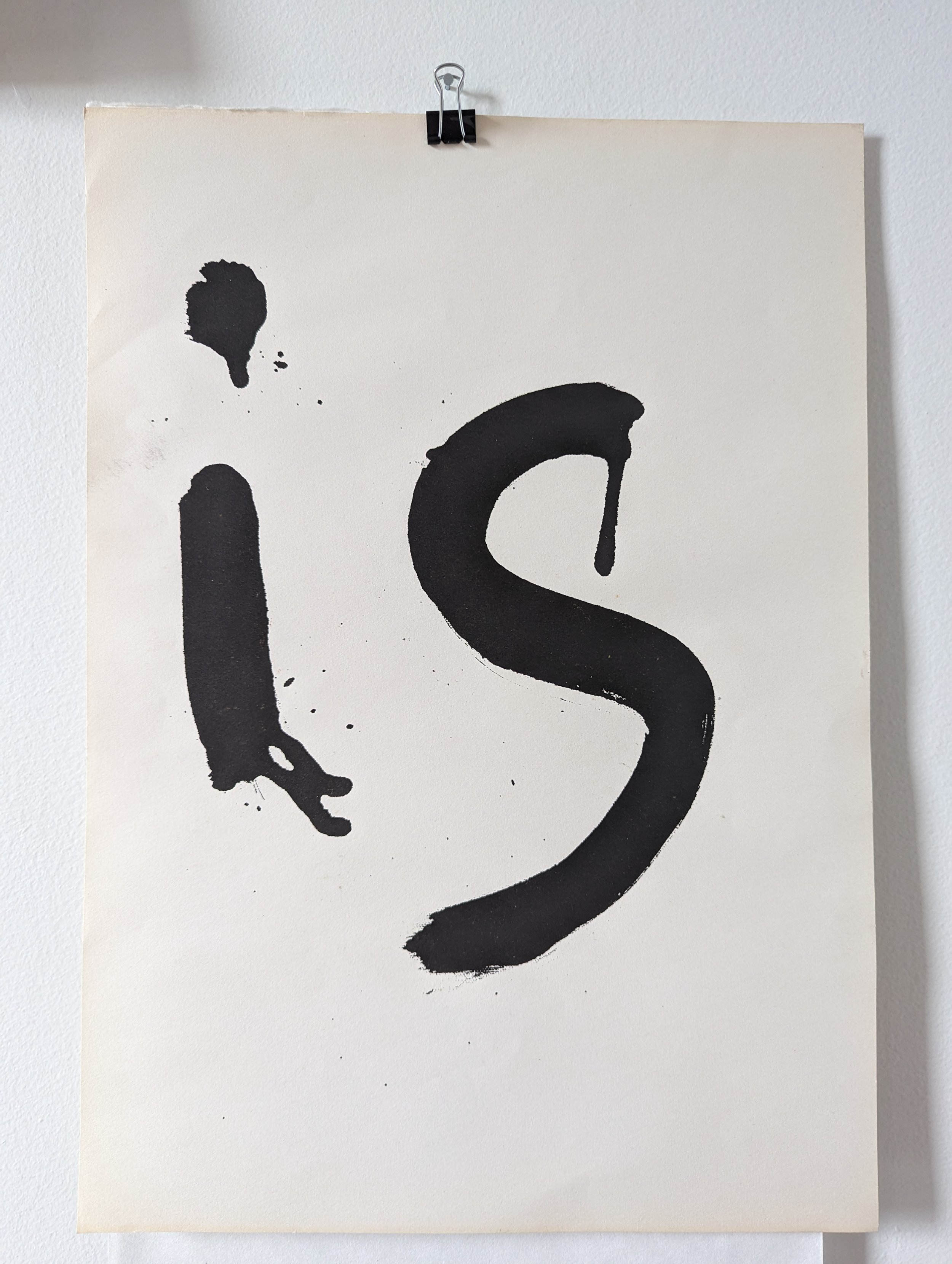

What began as a technical inquiry into microbial calcification, over the course of three months, became a lesson in patience, attention, and care. Working with S. pasteurii, soil, and eggshells, I followed protocols, waited through invisible stages, and made decisions as the process unfolded. Calcification emerged gradually, not as a single result but as an ongoing negotiation between living organisms, material conditions, and time. The forms that resulted record a process of learning—moments of uncertainty, adjustment, and wonder. They are not proofs, but traces of sustained engagement with a living system.

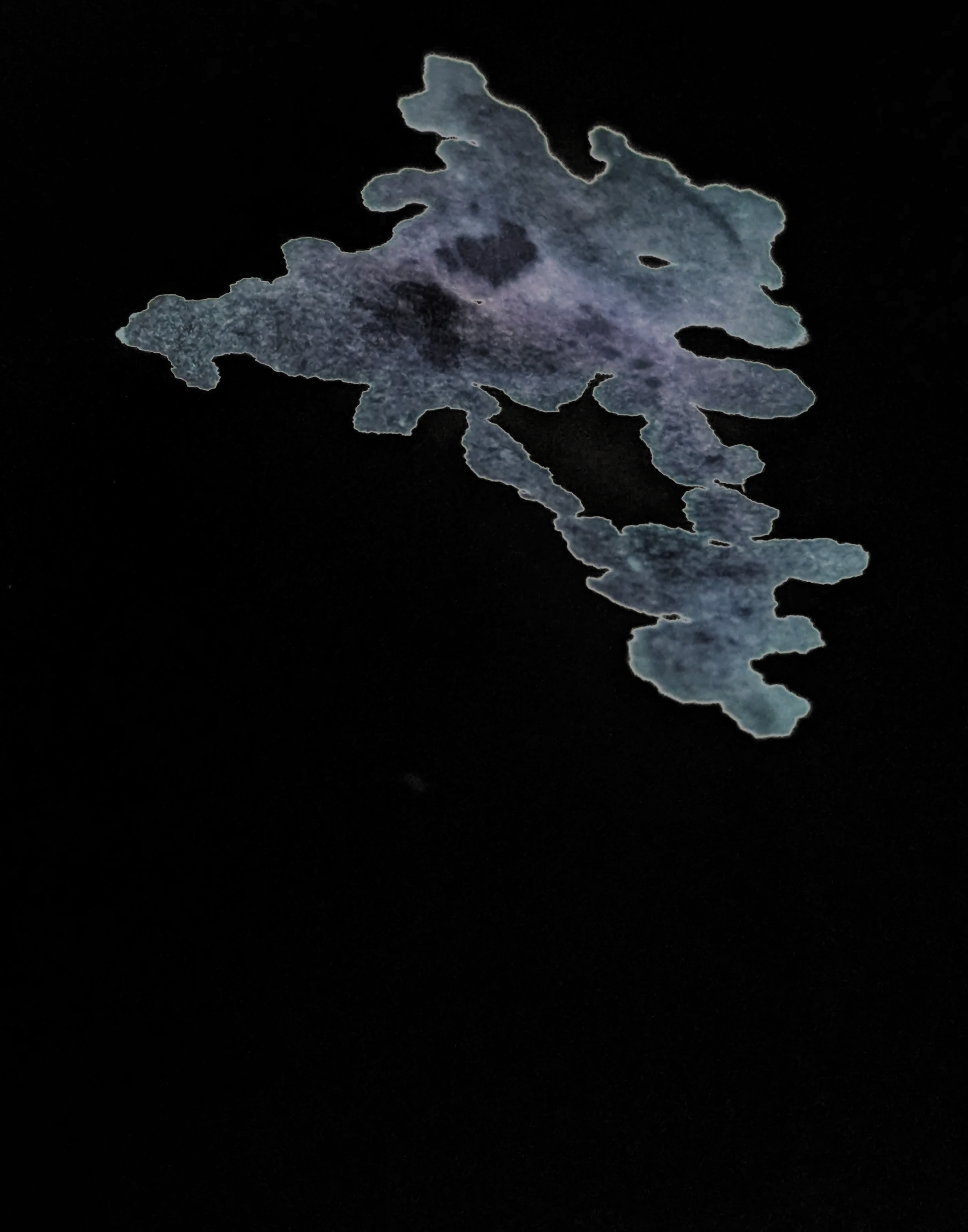

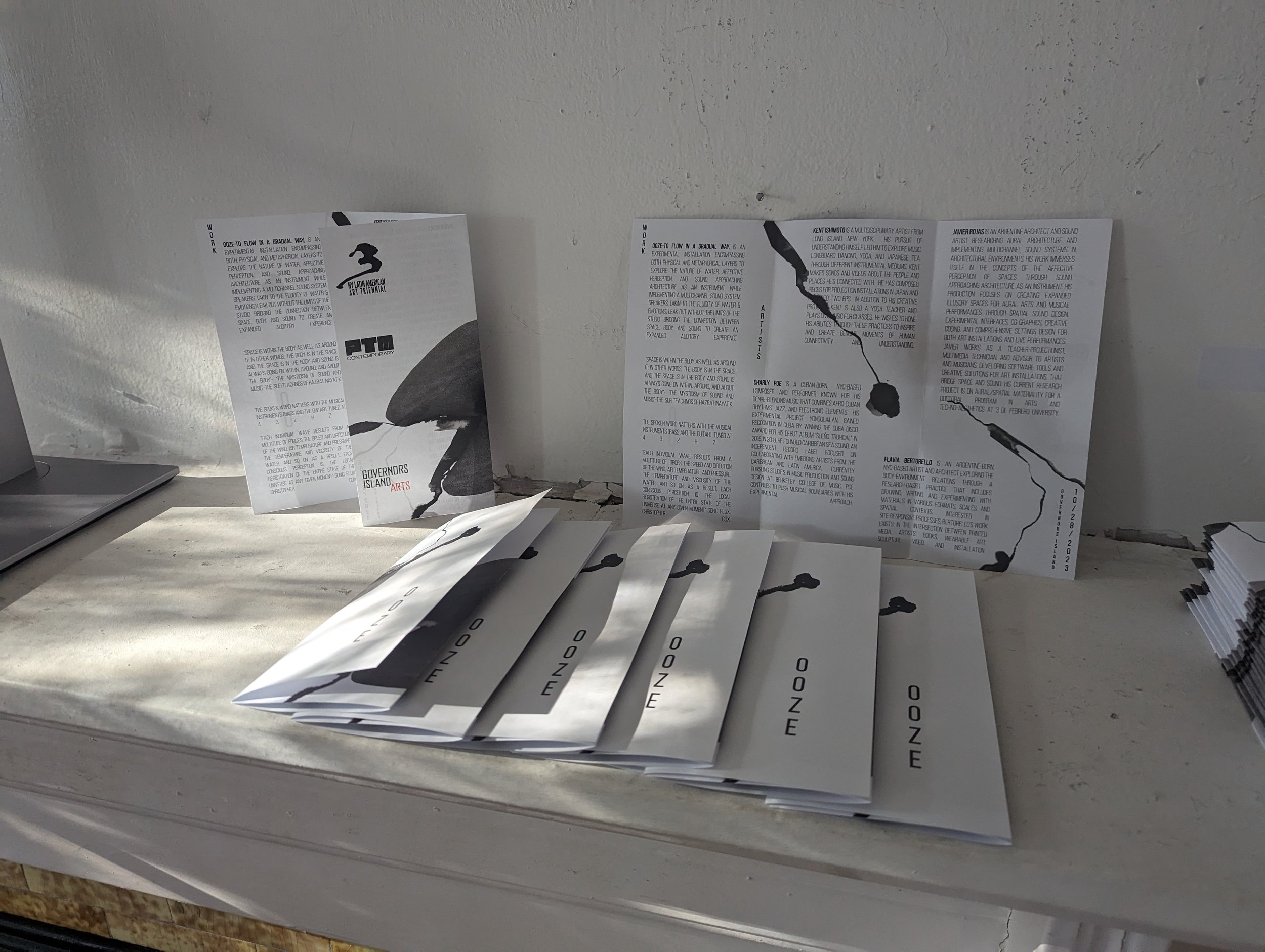

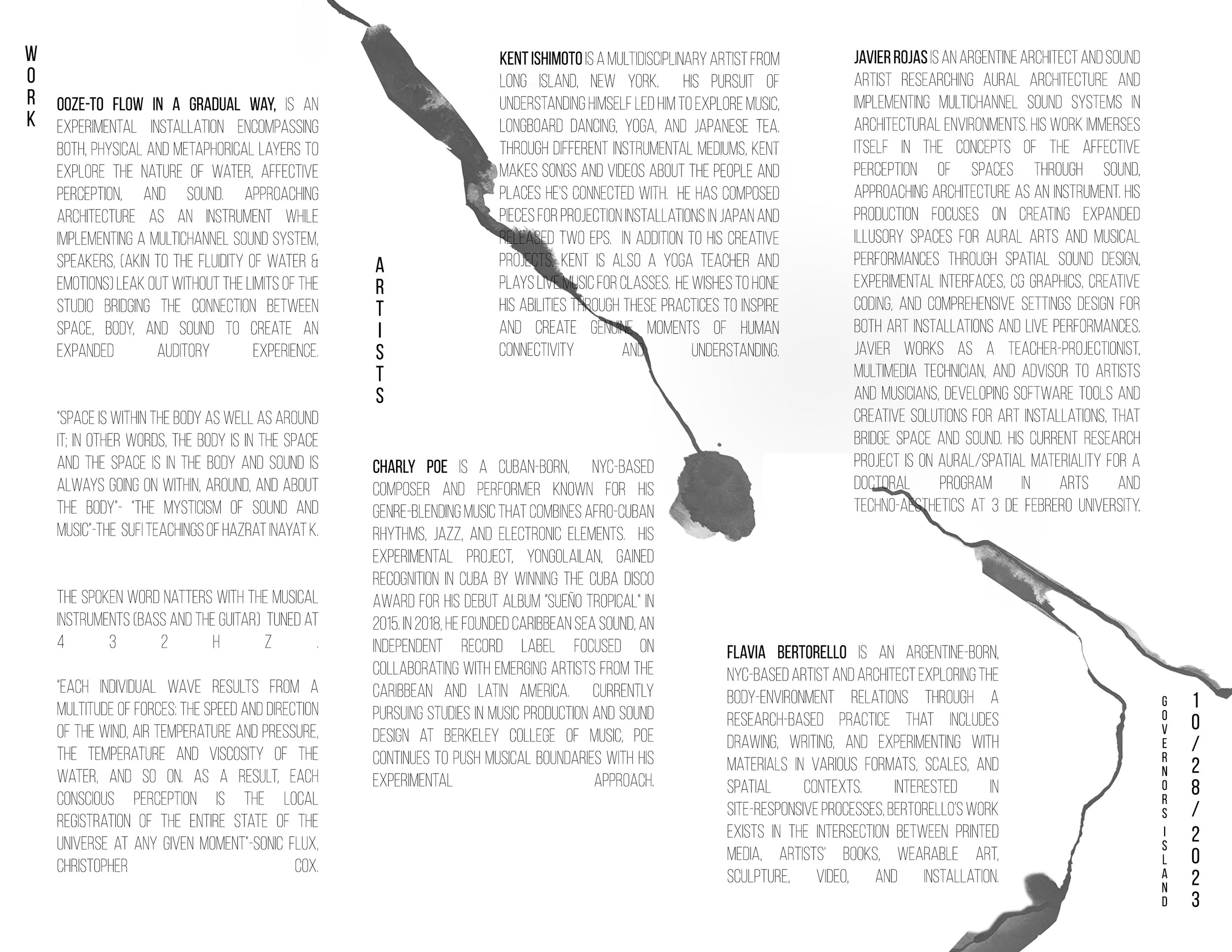

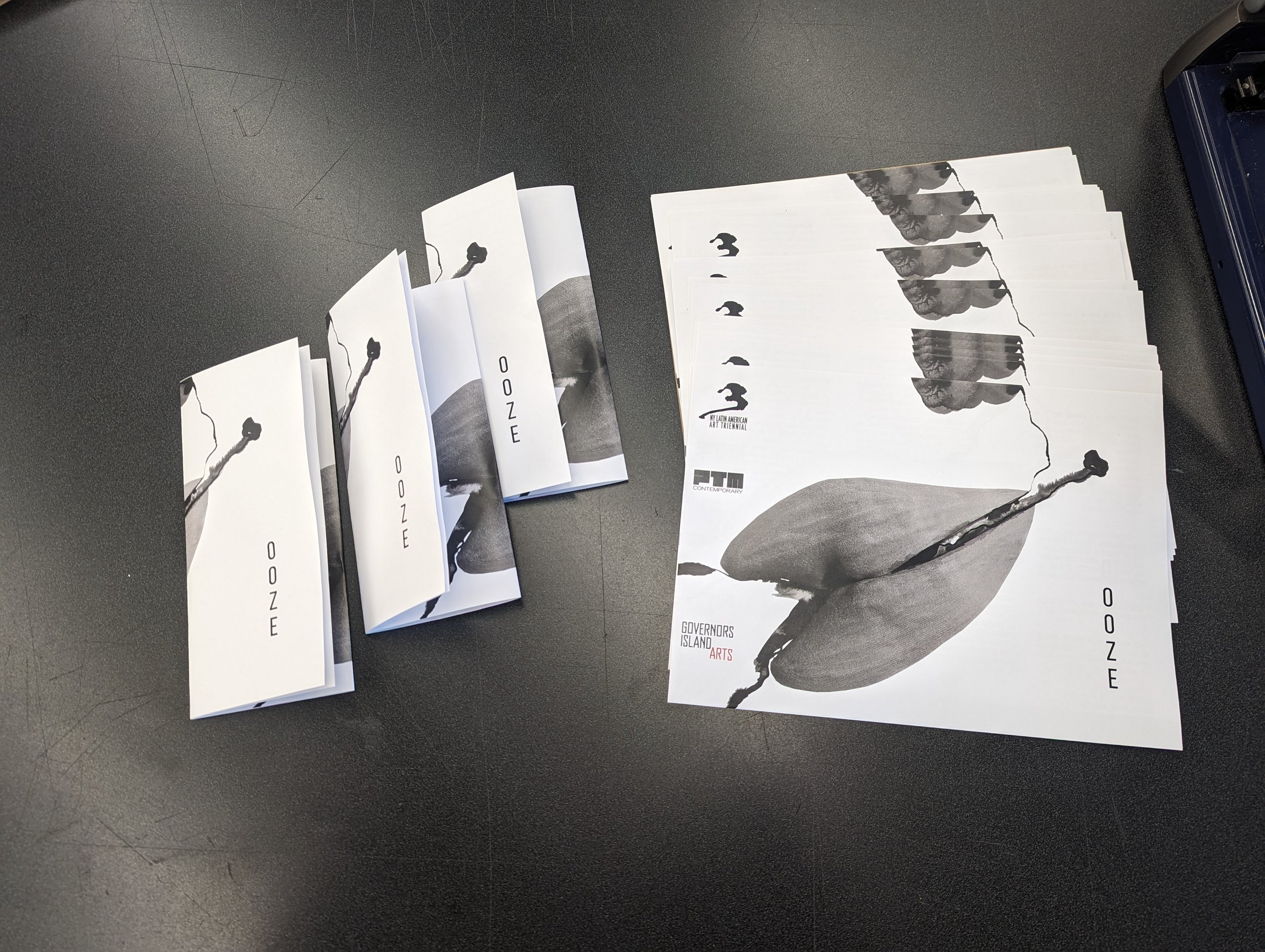

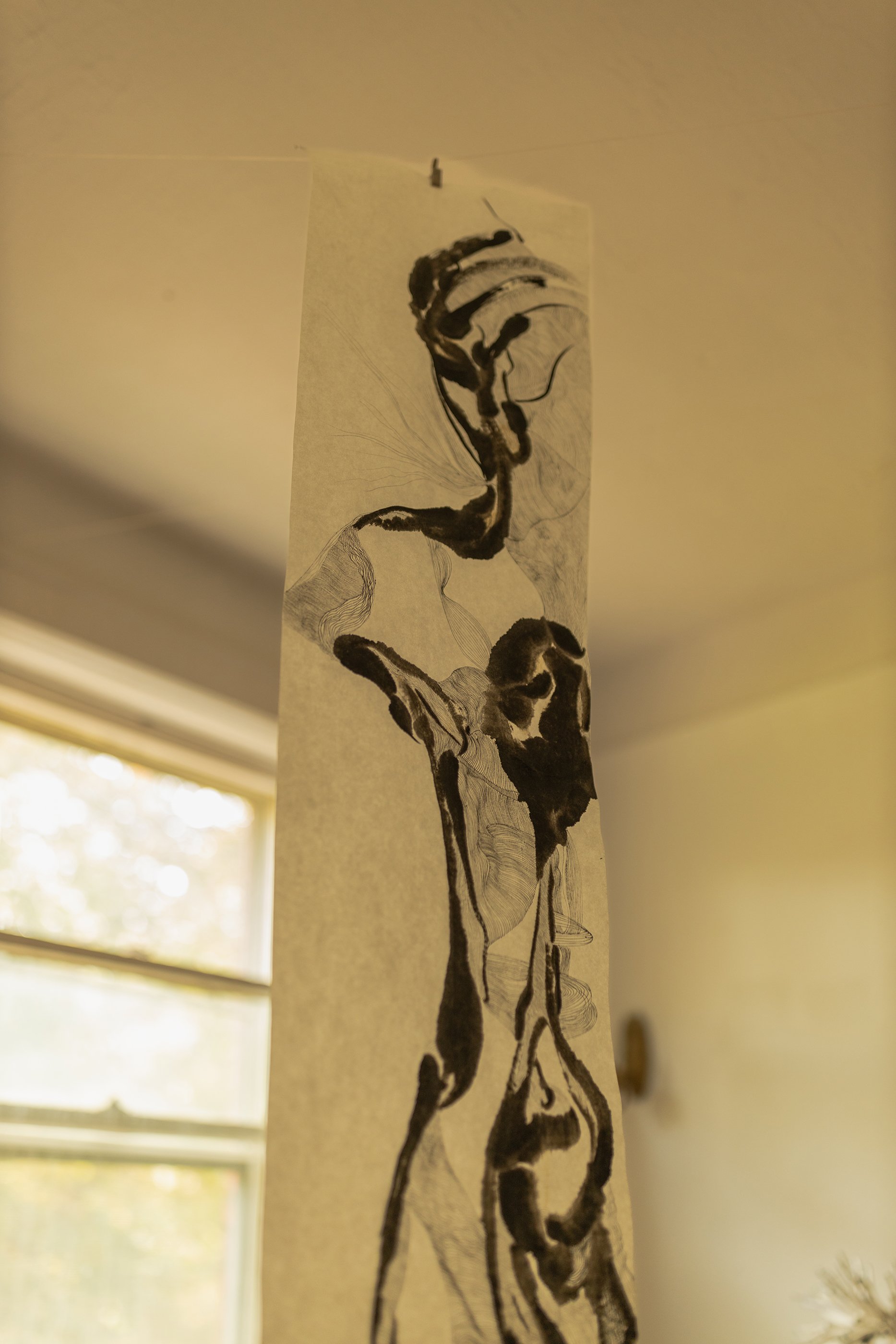

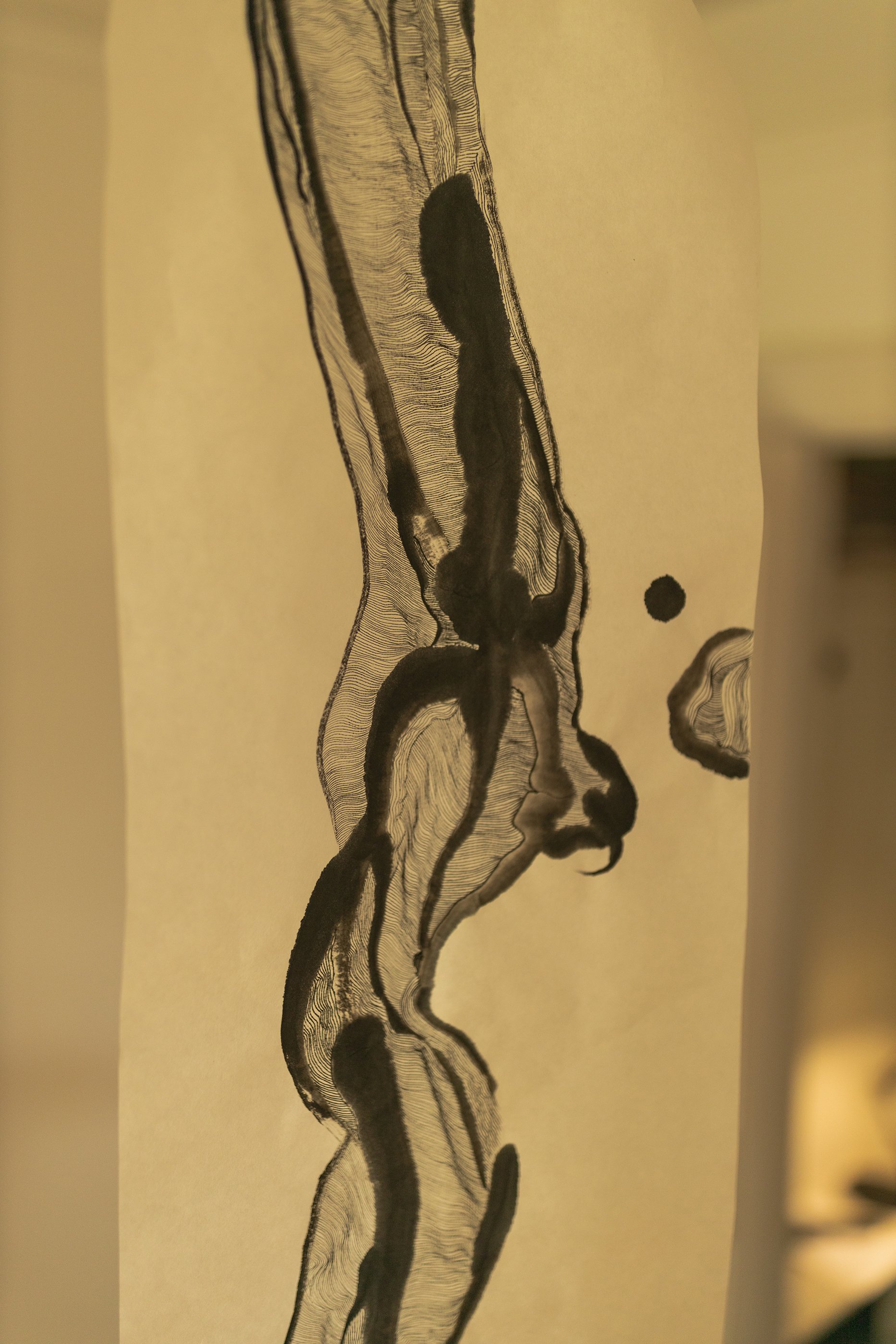

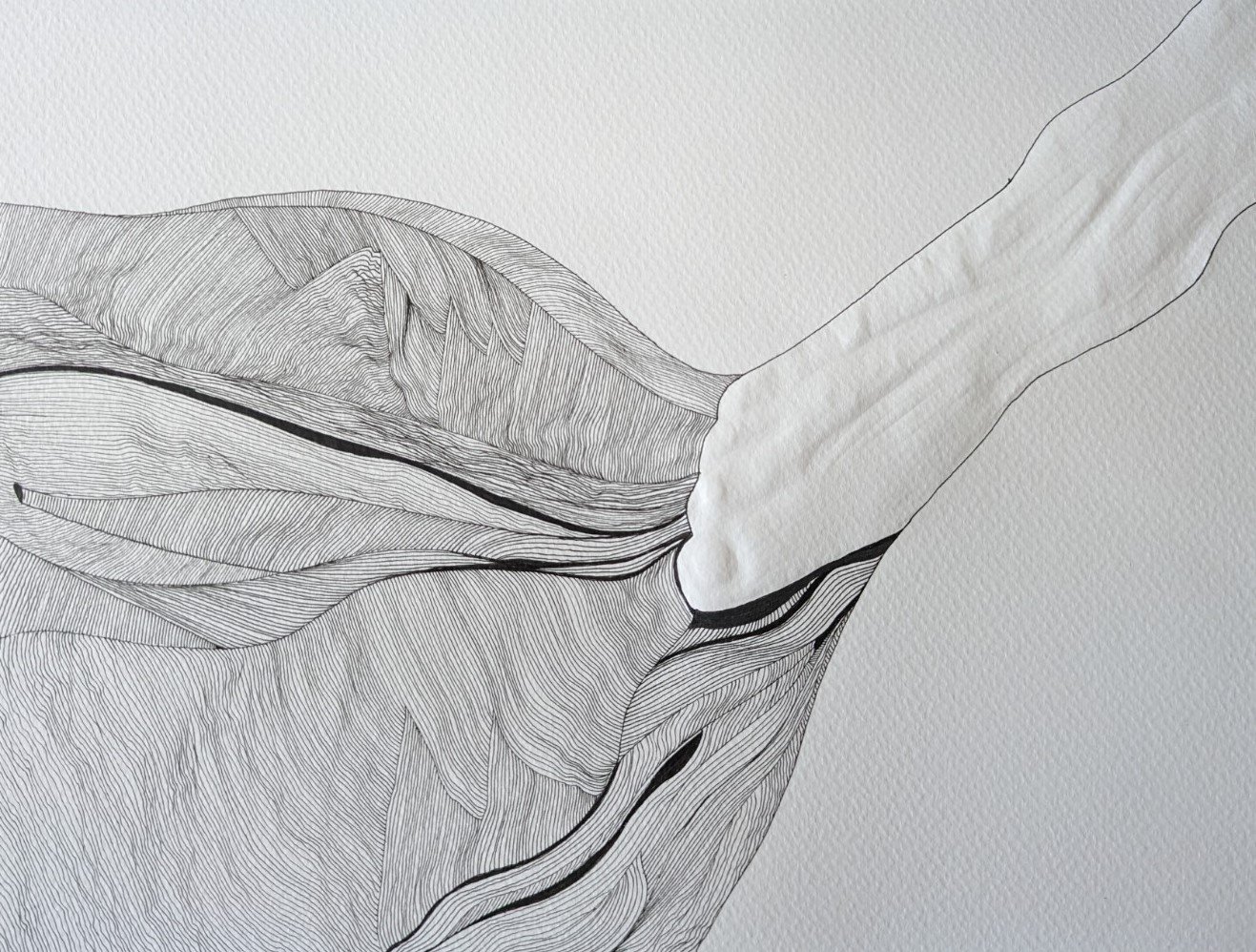

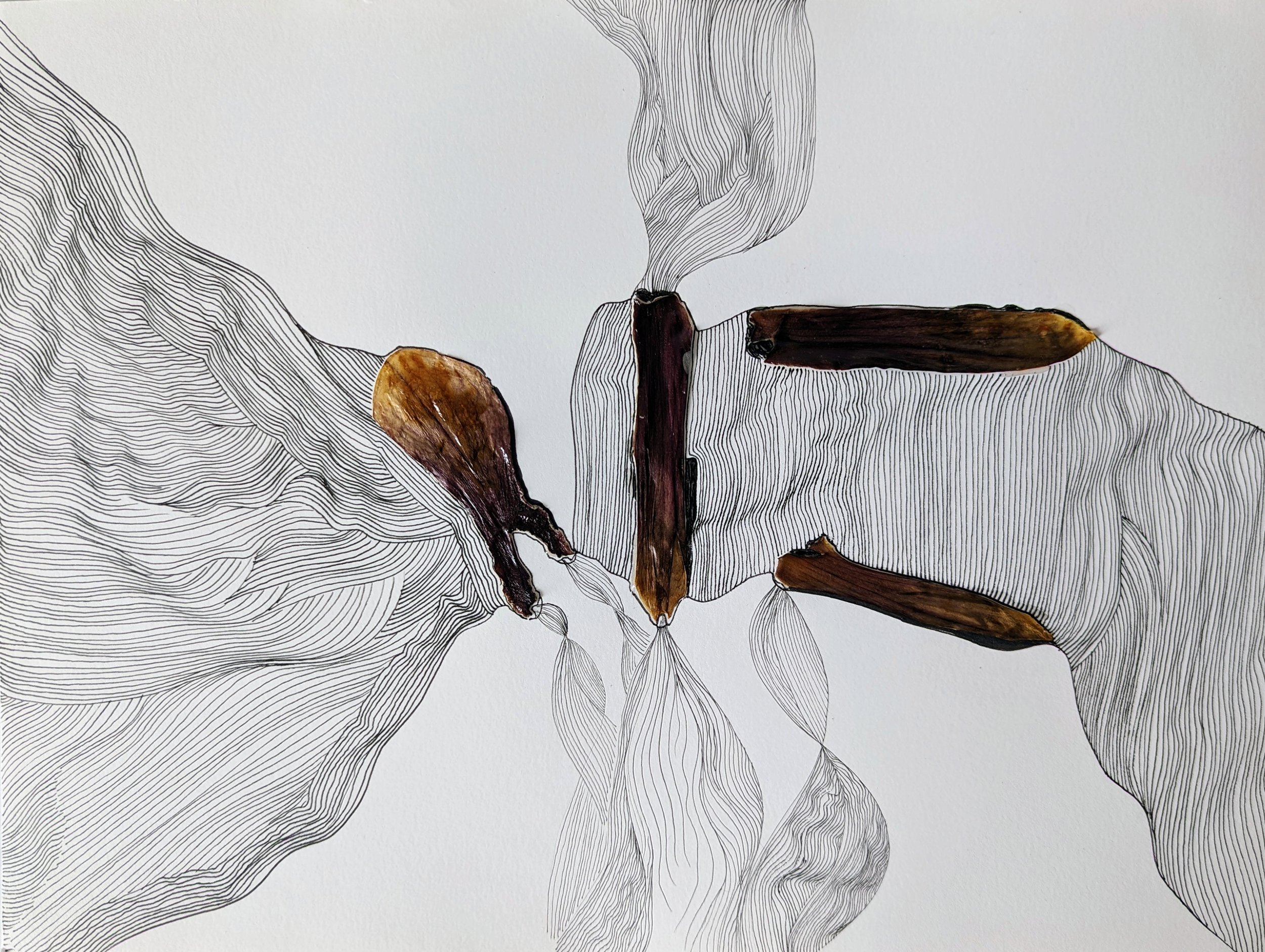

Ink on paper

Entering the Lab

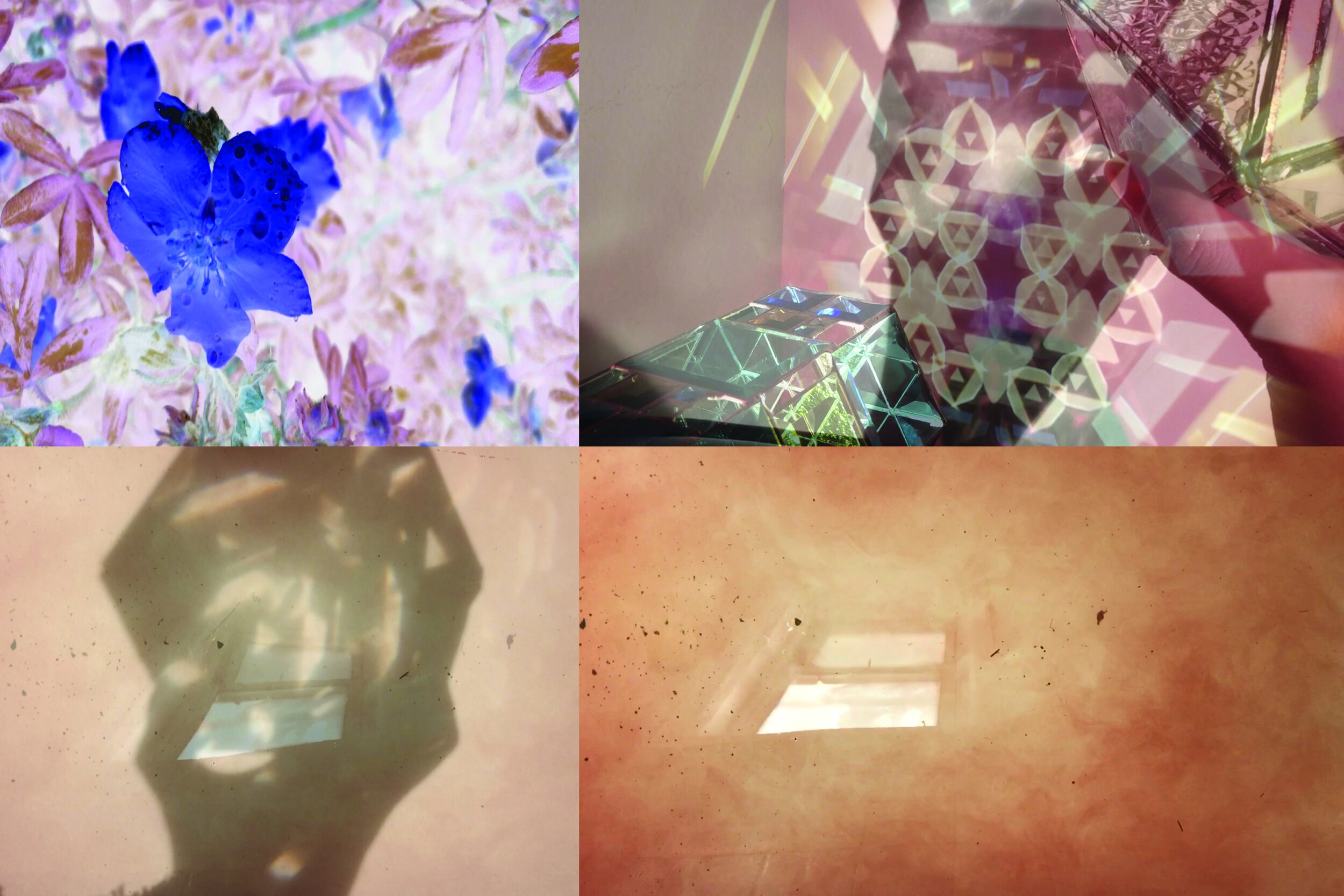

Entering the lab initially felt restraining. Almost immediately, however, I began to observe and wonder about every machine and object—the aluminum tables, the blue light that felt intimidating, the books and samples on the shelves. The space is tinted with blue light and carries the distinct smell of antibiotics. Every surface is measured, occupied, and used with purpose. Everything I encountered, from the language to the tools and techniques, was unfamiliar to me. In that sense, entering the lab felt like entering a completely new realm, coming from an art and architectural studio practice. Even the way I moved my body felt different.

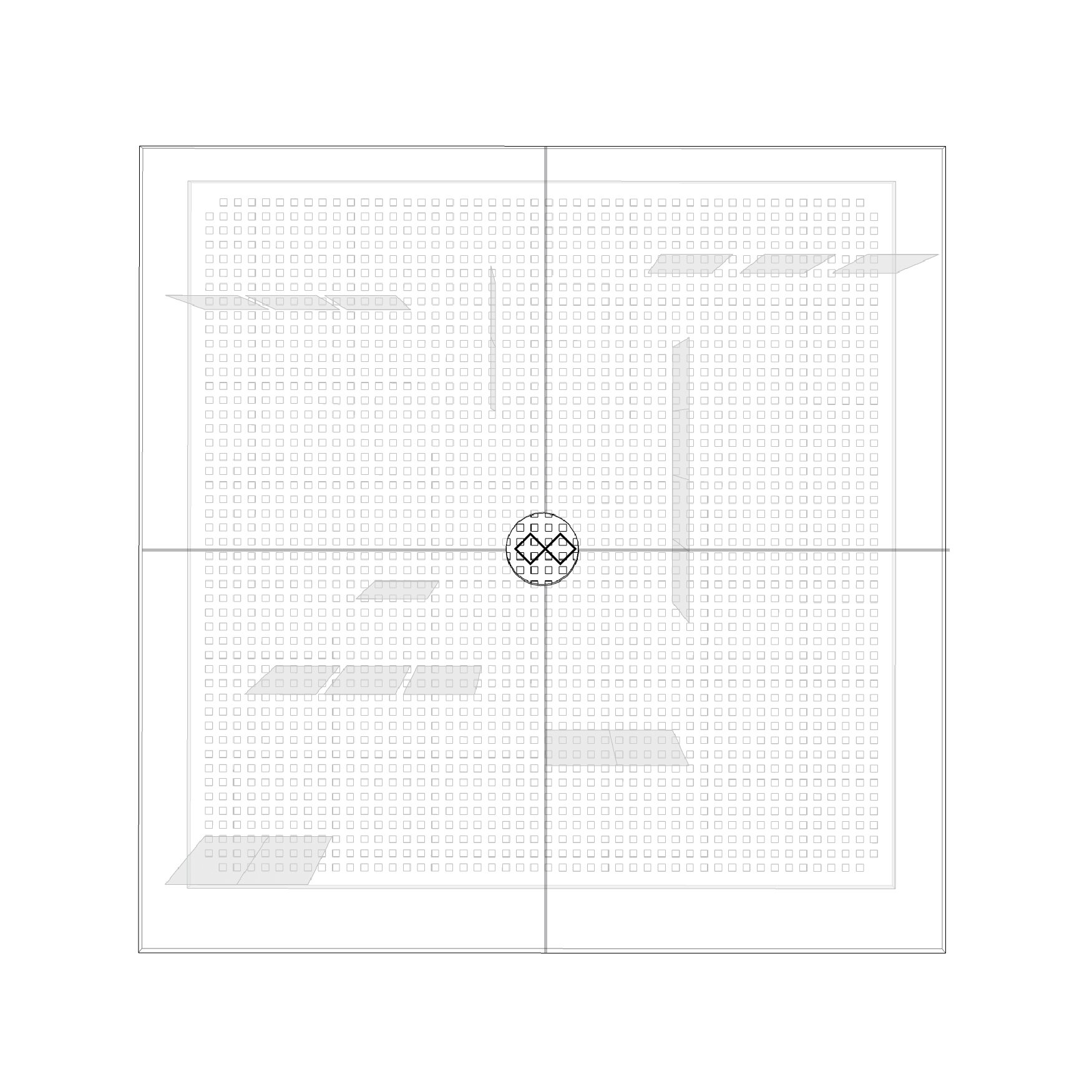

The first thing I noticed was that there is no space for wandering. Everything is intentionally placed. Every inch of the floor plan is planned—literally. The lab functions. This is where a part of me felt an immediate connection: the architect observing flows, points of connection, order, and chaos, all operating within clearly defined boundaries.

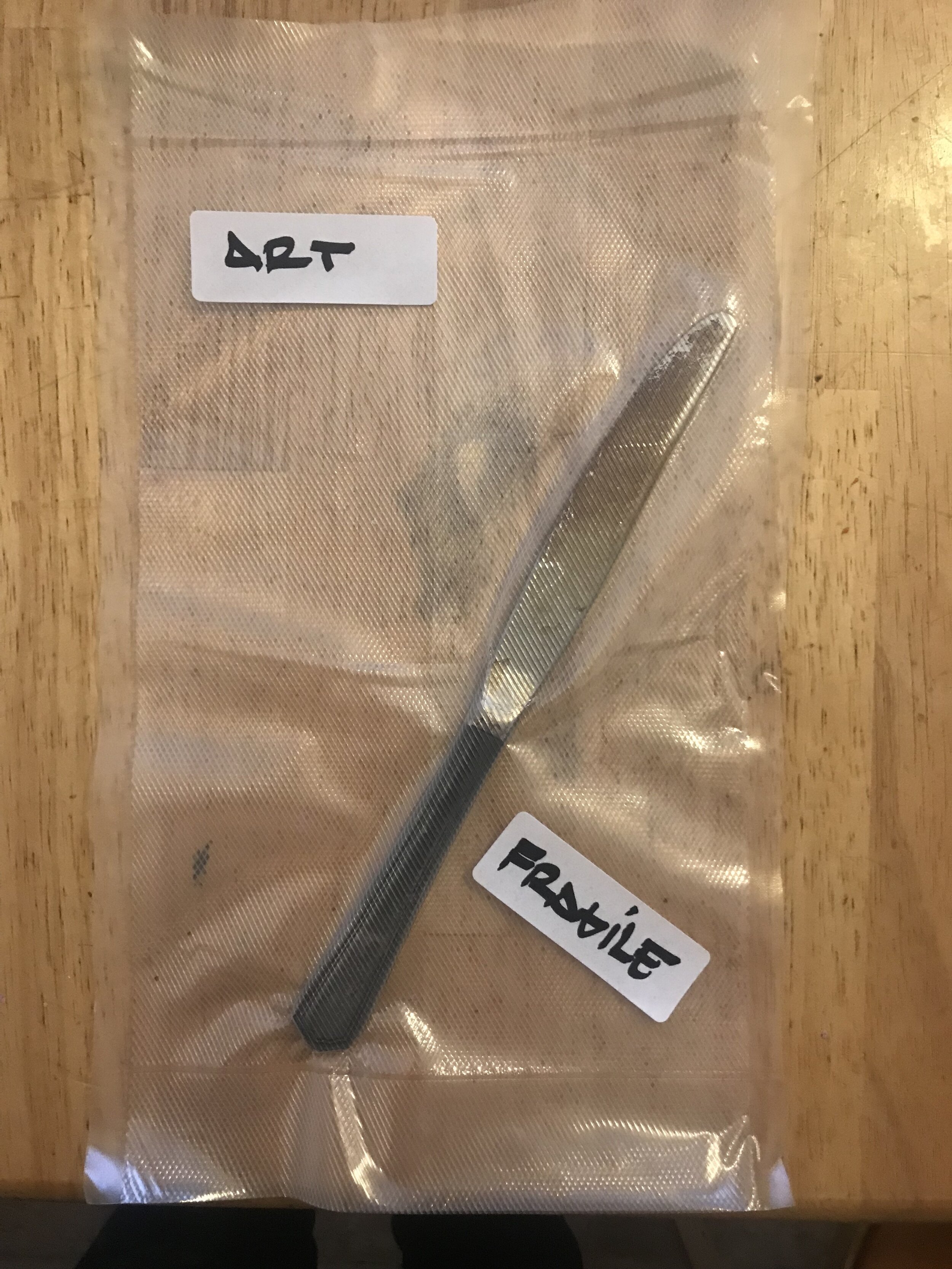

One of the first lessons I learned was how to be sterile. Wearing gloves at all times, no food or drinks allowed, cleaning surfaces with 70% IPA alcohol, understanding where and how to dispose of different types of waste—these practices slowly became familiar. I learned how cleanliness in the lab is not aesthetic, but operational. My favorite machine quickly became the autoclave: a device that functions like a super-powered pressure cooker, using high-pressure steam to sterilize equipment and materials by exposing them to temperatures above boiling point achieving near-total sterility.

the autoclave @genspace

Learning to read protocols marked another turning point. Scientific language can be dry, even alienating at first, yet it demands careful attention. One of the first protocols I learned was the ten-fold dilution. Pipetting required an entirely new understanding of scale—of size, volume, and quantity. Measuring challenged many of my assumptions, particularly how a milliliter shifts meaning depending on the container holding it.

The lab demands full attention, which is why working in pairs becomes essential. As we say in architecture, four eyes see more than two. Science, too, unfolds most clearly through collaboration. Working with living systems introduces a unique awareness of co-creation—working alongside another agent, even when that agent is a unicellular organism. This realization felt humbling and deeply engaging.

Much of what happens in the lab unfolds beyond immediate perception. Many processes require waiting—36 hours or more—before any evidence of change becomes visible. In this context, vision and touch, so central to architectural and artistic practice, recede. Attention shifts instead to time, conditions, and trust in processes that operate beyond the scale of direct observation.

Soil as Habitat

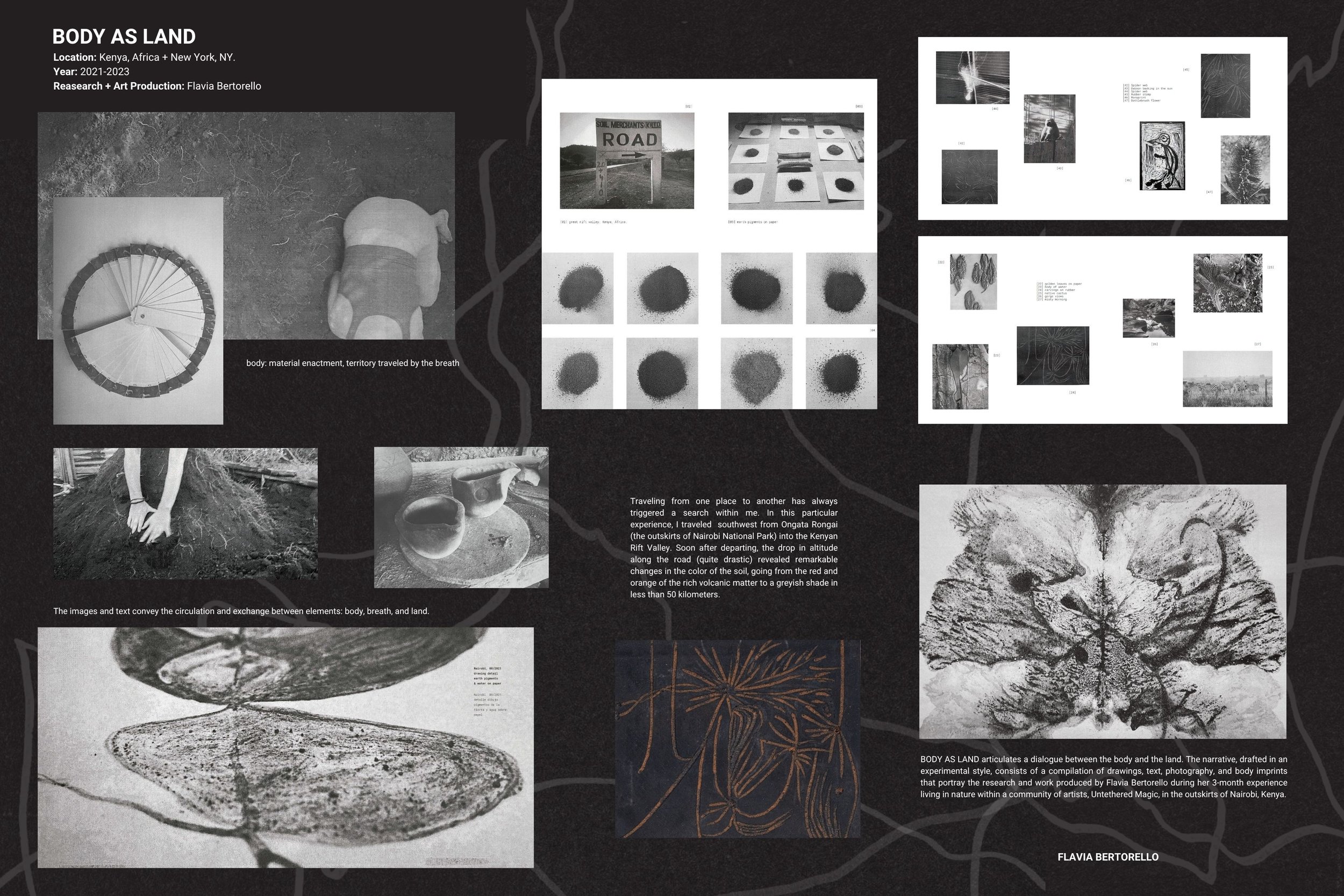

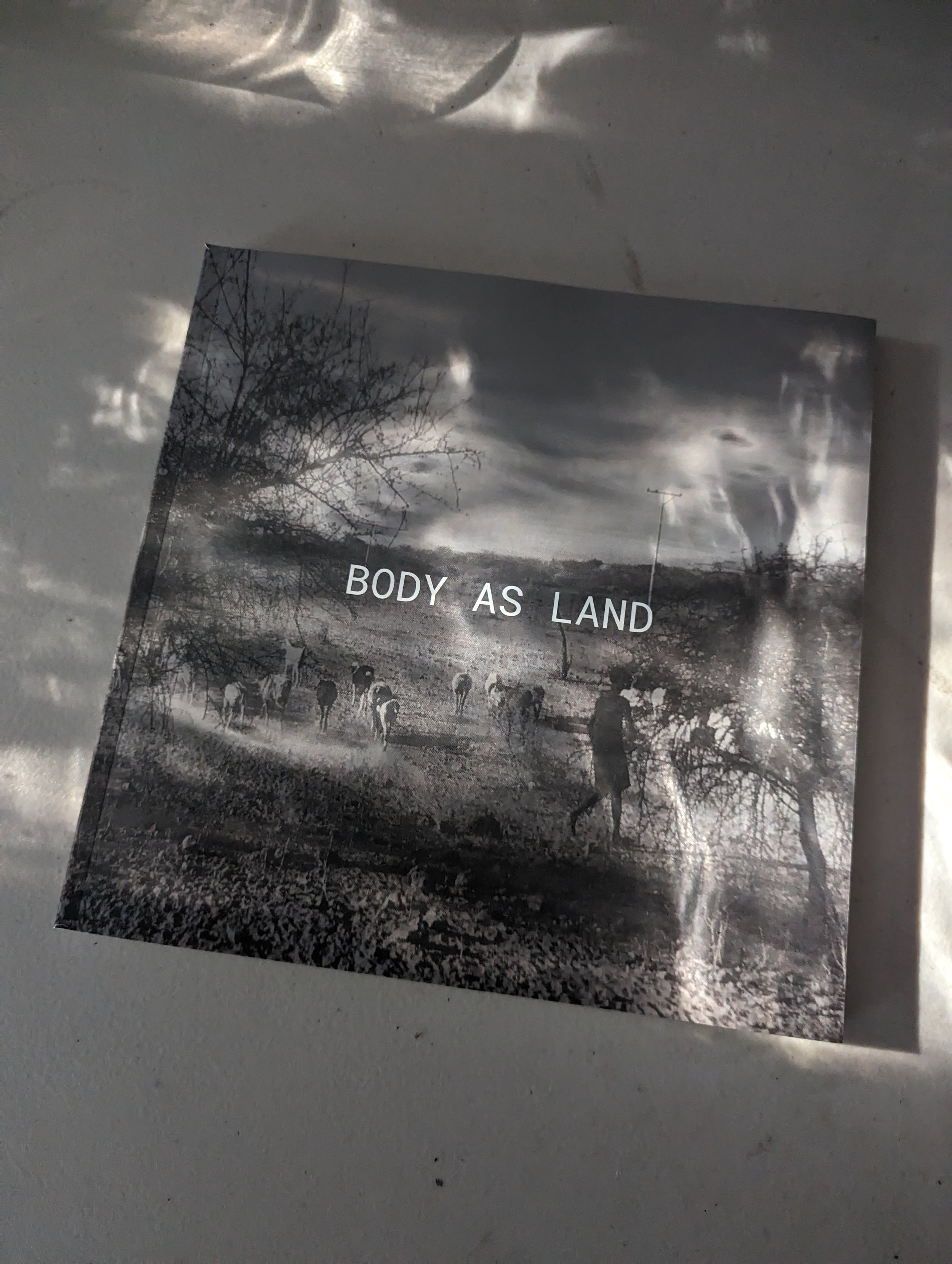

Long before soil became part of an experimental process at the lab, it was already central to my practice. In 2021, I spent time living on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya, where I experienced a profound and embodied connection to land and ground. From that experience, a new body of work emerged—Body as Land—in which I engaged with soil both as material and as metaphor. Working directly with the ground revealed a fundamental realization: our bodies are tethered to the earth. Soil was no longer something beneath me; it was something I was in constant exchange with.

Body as Land

Returning to New York after this experience was not seamless. I remember having vivid dreams, even crying in my sleep, missing the land. What I had felt in Kenya was not only a connection to place, but a sense of wholeness in my experience of being. Back in the city, that intimacy with soil felt interrupted. In urban environments, it is easy to remain disconnected from the ground—our bodies move across pavements, manholes, concrete slabs, and infrastructures that mediate nearly every interaction with the earth. Soil is present, but rarely touched.

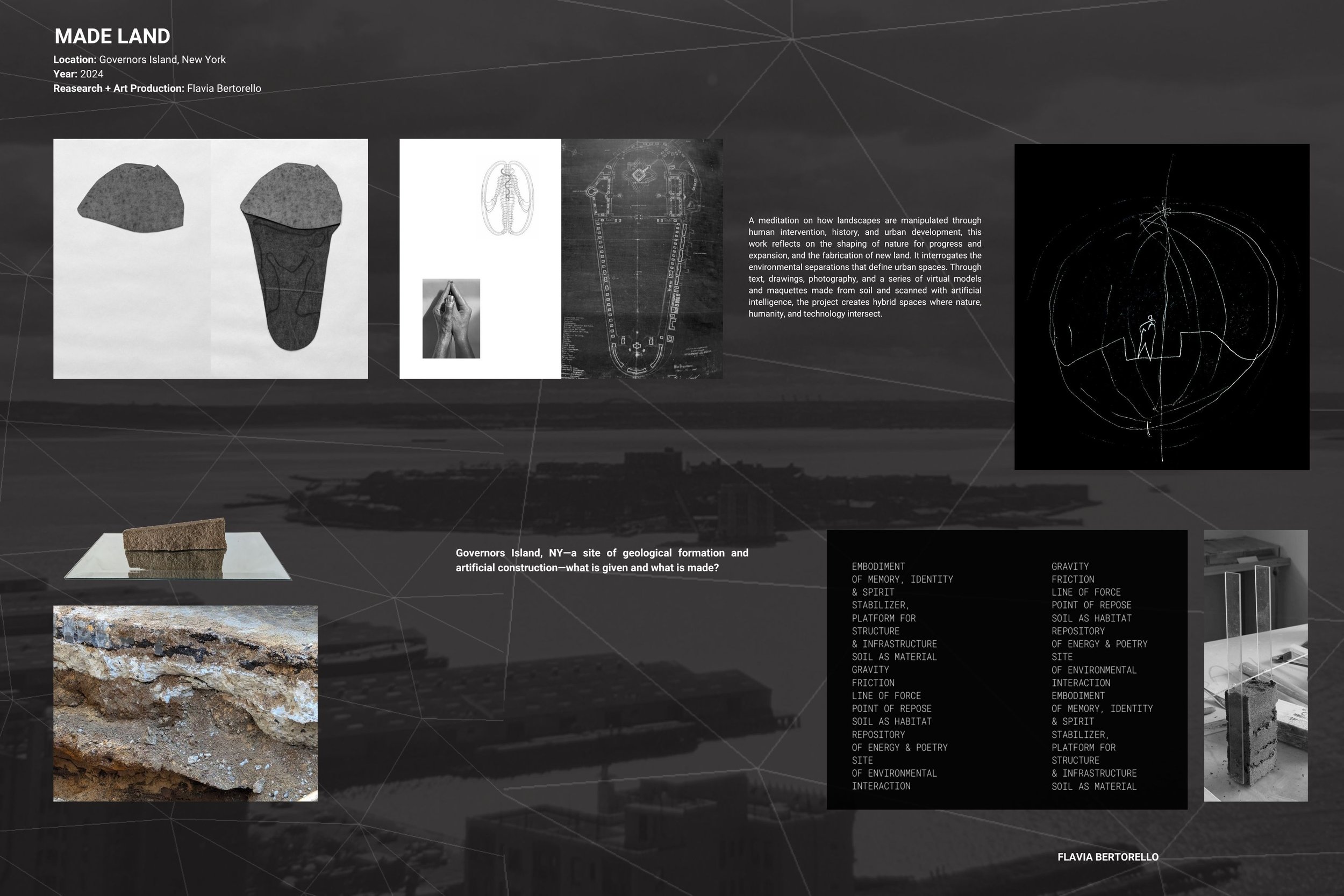

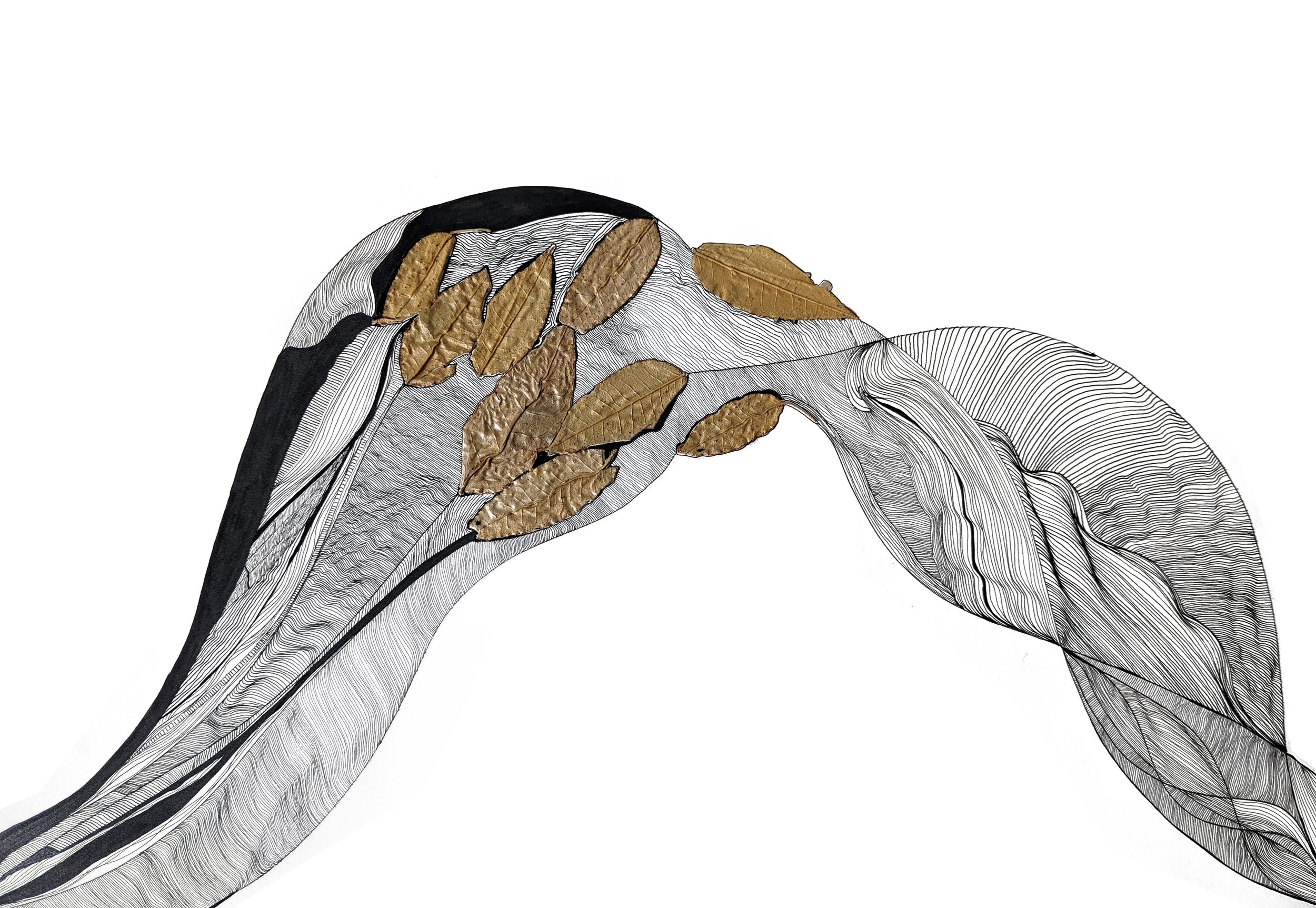

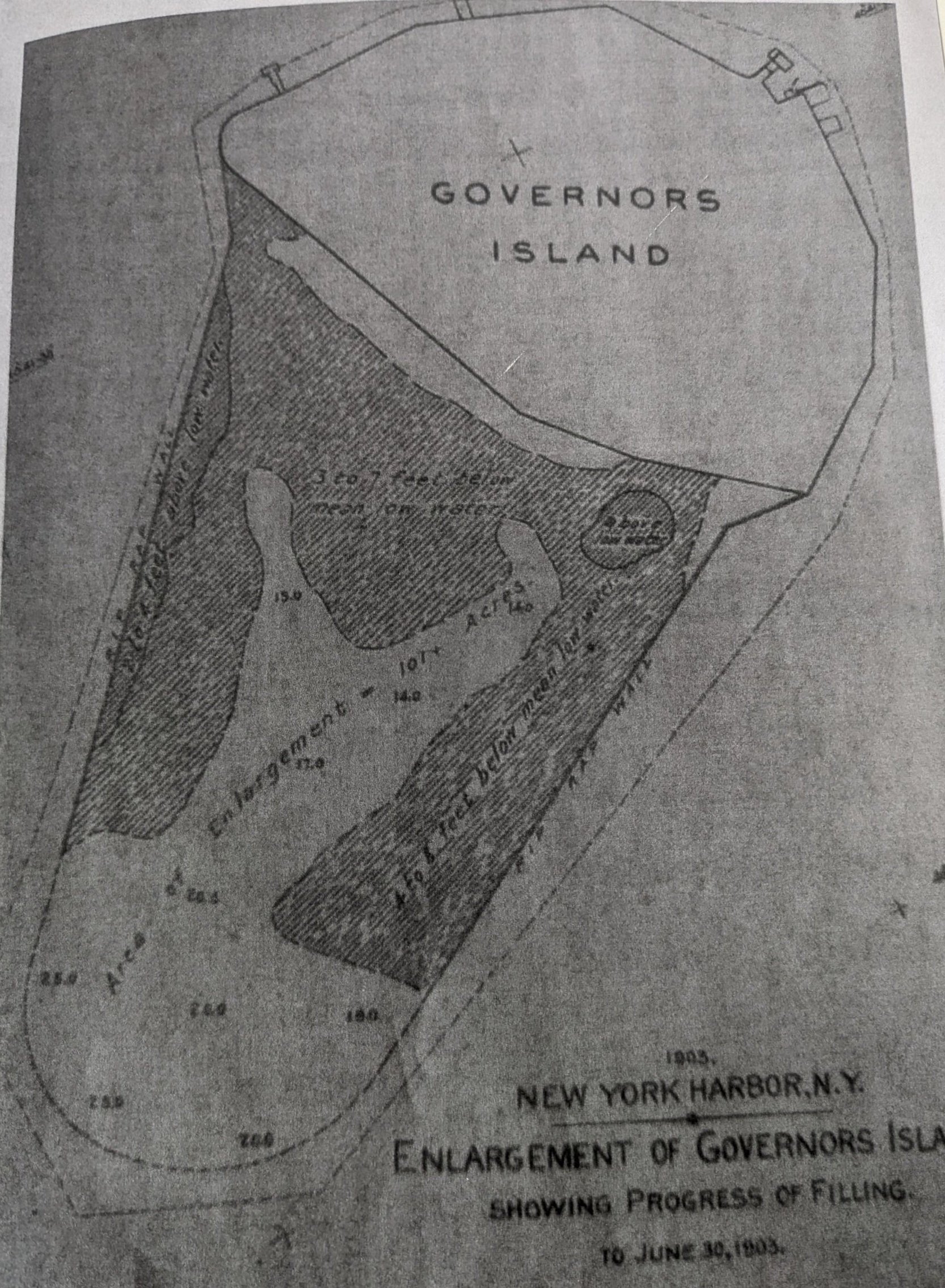

I continued working with soil in New York, this time confronting its urban condition. I began researching NYC soils—their taxonomy, geological formation, and layered histories. This inquiry led to Made Land, a second body of work reflecting on the manipulation of soil in urban contexts. The term “made land” refers to anthropogenic fills: soils constructed, displaced, and reassembled through human activity. During a residency at the Urban Soils Institute, I meditated on soil not only as material, but as infrastructure—an embodiment of gravity and repose, a repository of memory, a habitat, and a site of environmental interaction. What was once considered purely natural is now deeply entangled with human debris, construction, and waste. This realization sharpened both my sense of connection to the earth and my awareness of separation.

Made Land

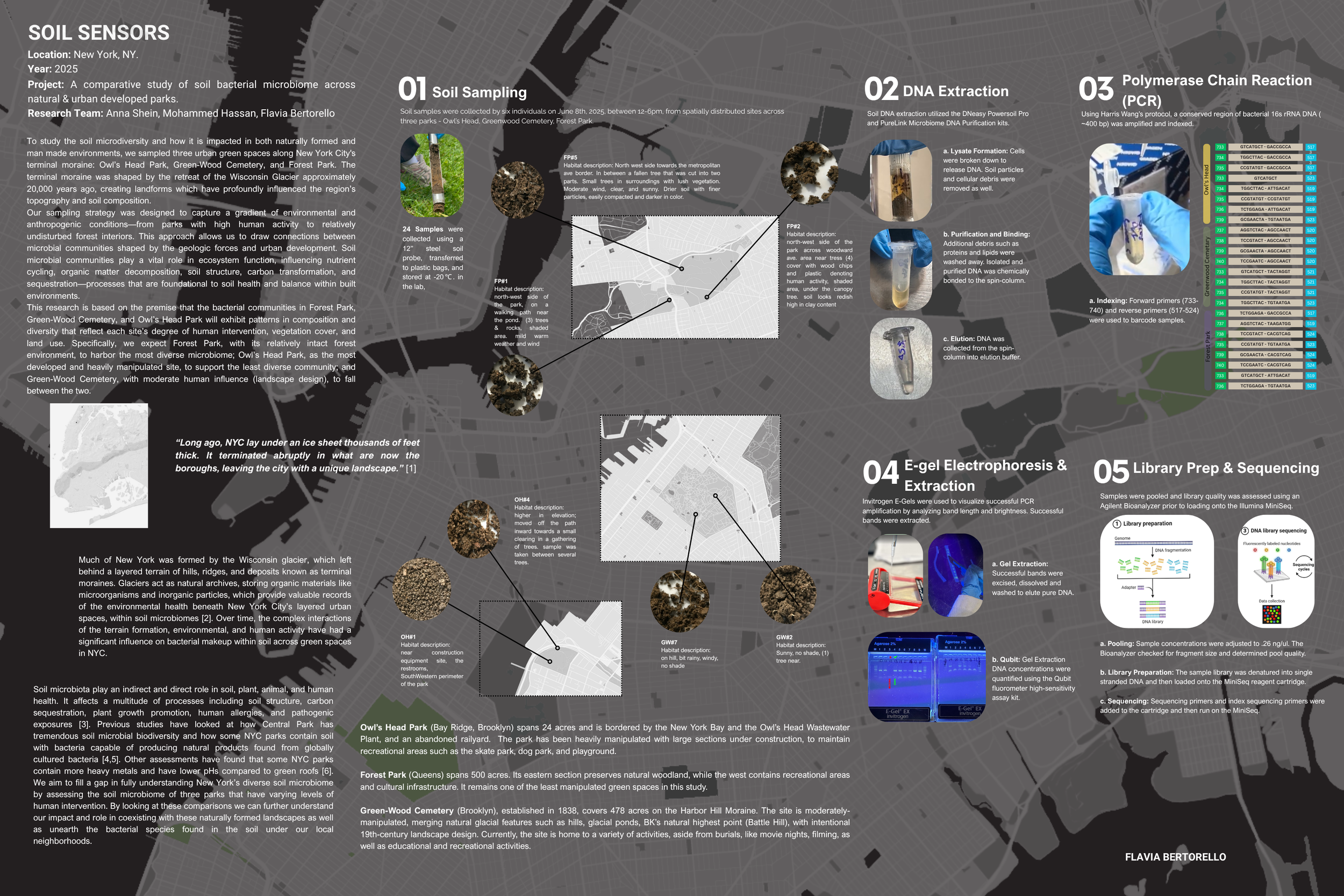

As my research continued, I became increasingly interested in soil not as a neutral base, but as a dense ecology—already alive, active, and relational. Through a fellowship at Genspace, I conducted a comparative study of soil microbiomes in three New York City parks, extracting DNA samples to better understand the bacterial communities that populate urban soils. This work introduced me more directly to the unseen microbial world that sustains the ground beneath our cities.

Bacteria mediate the exchange of matter and energy in soil—breaking down organic material, fixing and releasing nutrients, and transforming waste into forms that can be reabsorbed into living systems. In urban soils, microbial life operates much like a metabolic system, linking natural cycles to human-altered environments. Just as gut microbes sustain bodies, soil bacteria sustain the living ground beneath cities. This understanding deepened my interest in how bodies and cities metabolize matter, waste, and ultimately time.

soil sensors:

In cities, one must dig through layers of human fabrication—concrete, asphalt, pipes, and debris—to reach the earth beneath. Urban soil often lies hidden just inches below the surface, disconnected from visible natural flows yet continuously active. This condition complicates the relationship between body and ground. Soil, among its many functions, also acts as a medium that absorbs, conducts, and neutralizes forces—including the electromagnetic fields generated by our bodies—further reinforcing its role as an active interface rather than a passive support.

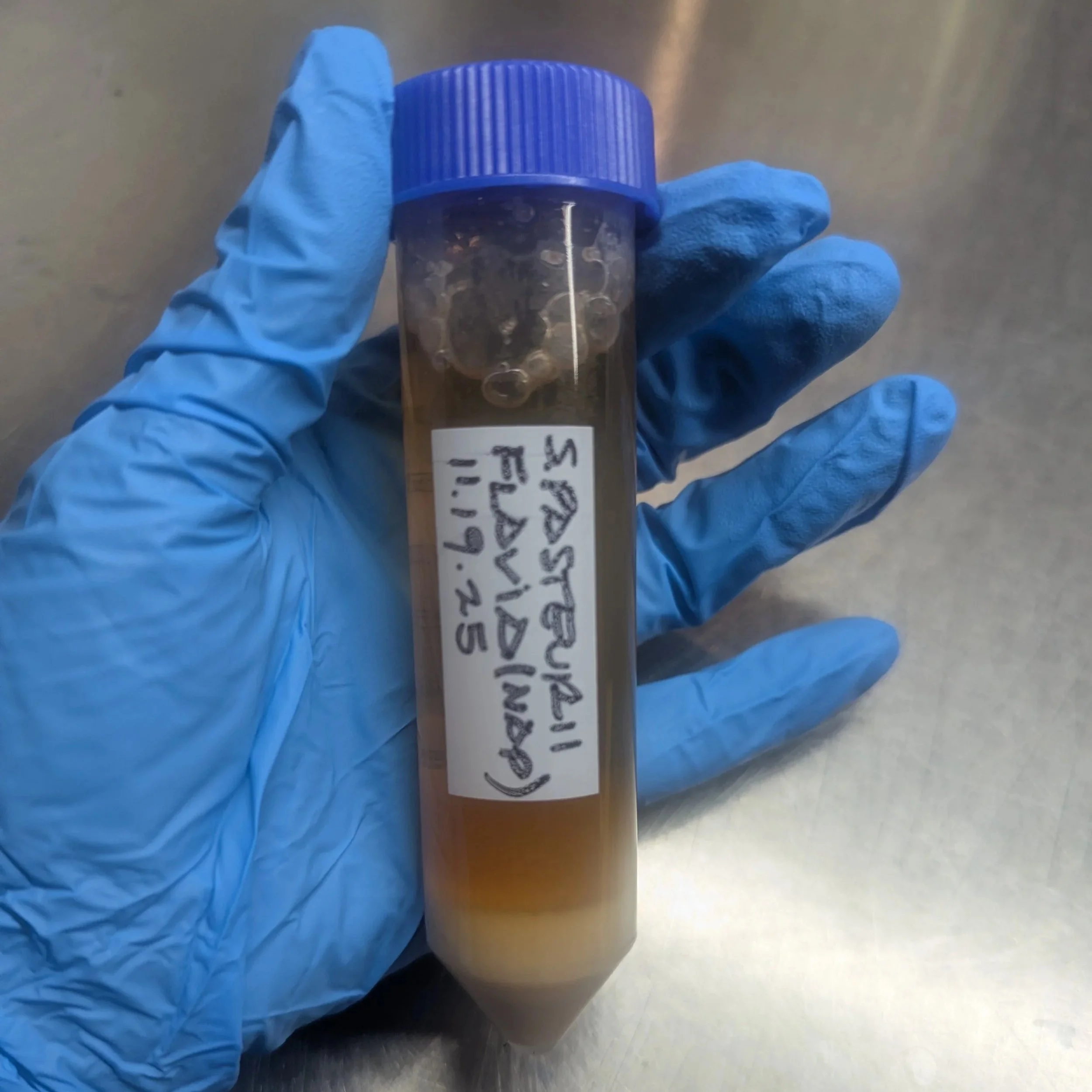

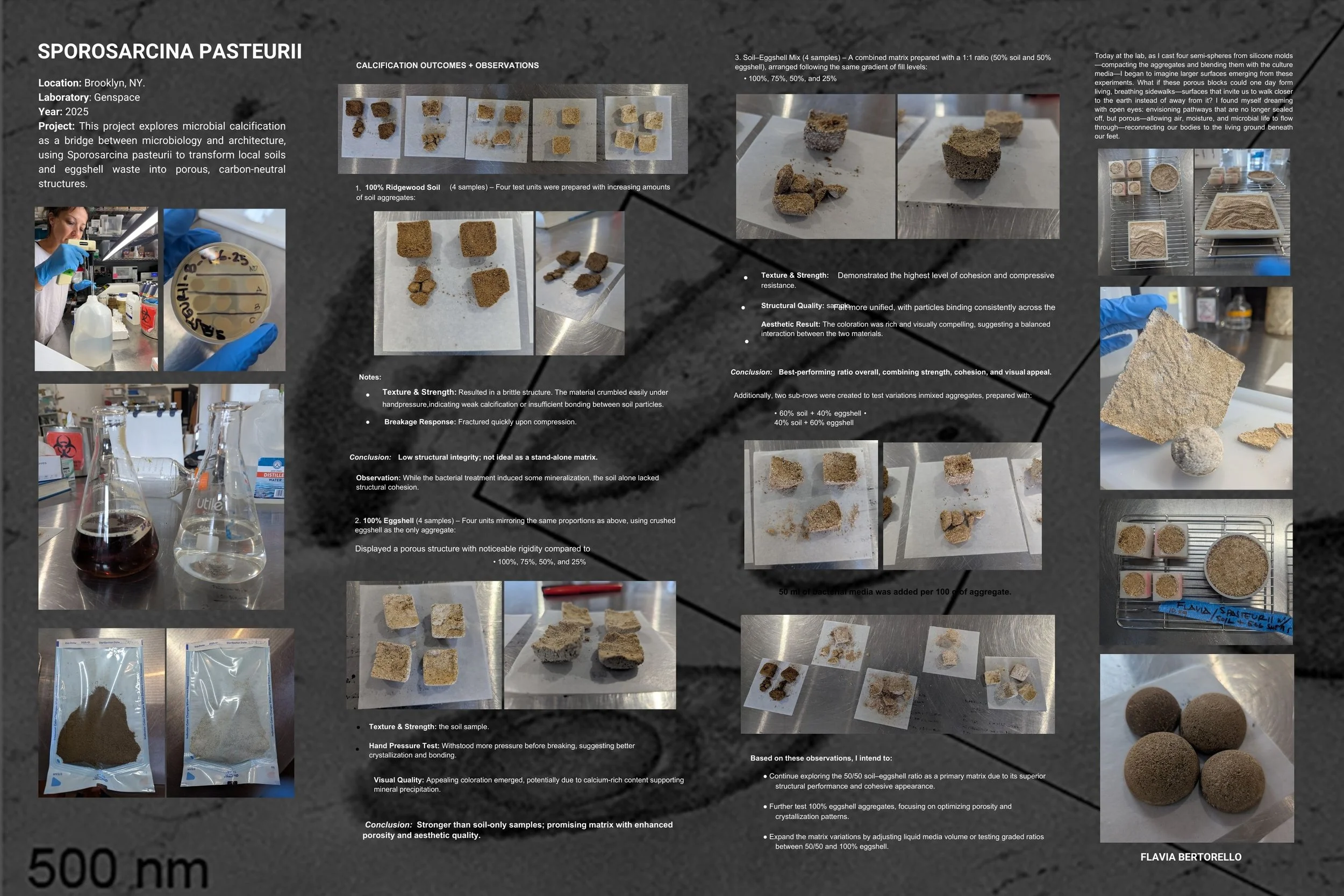

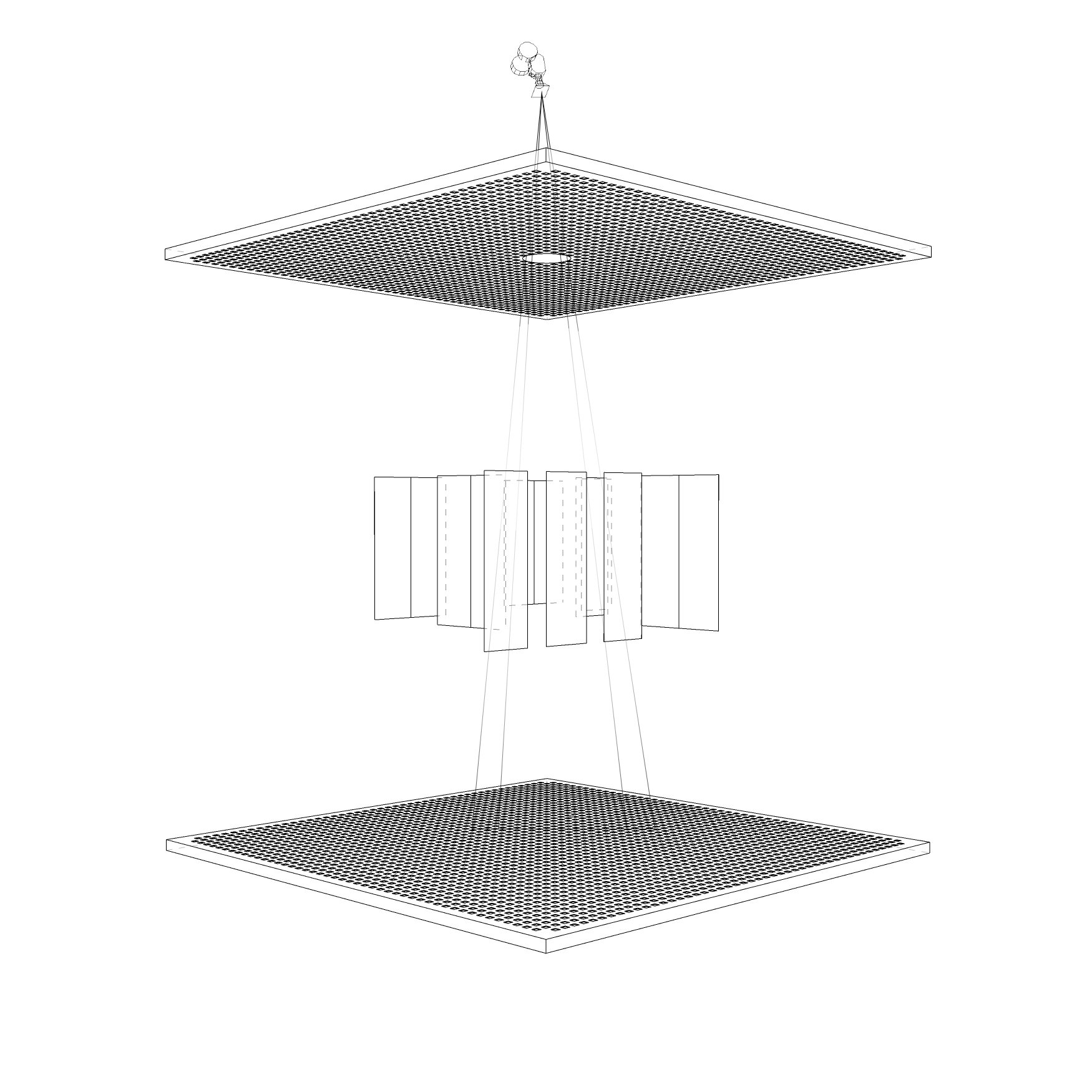

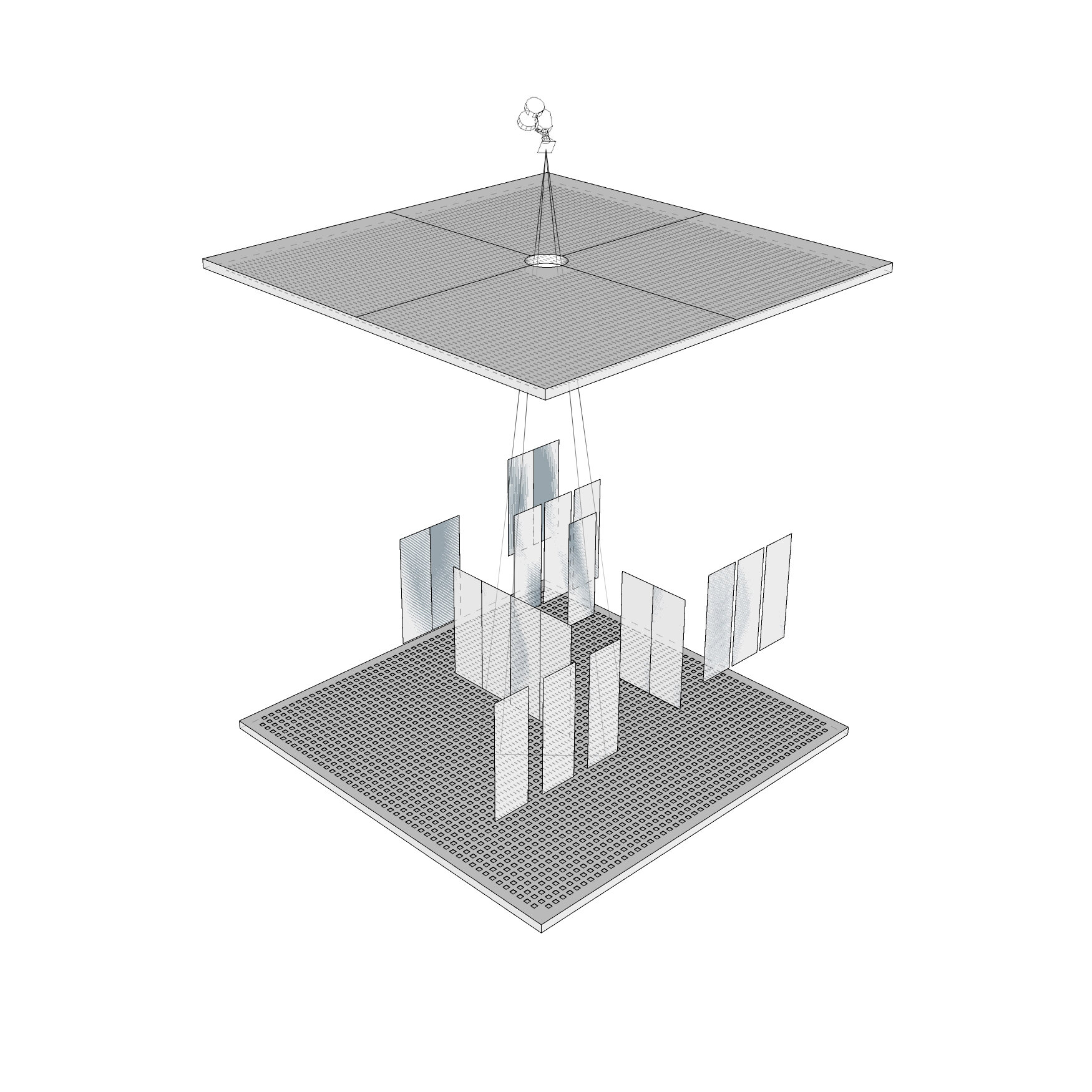

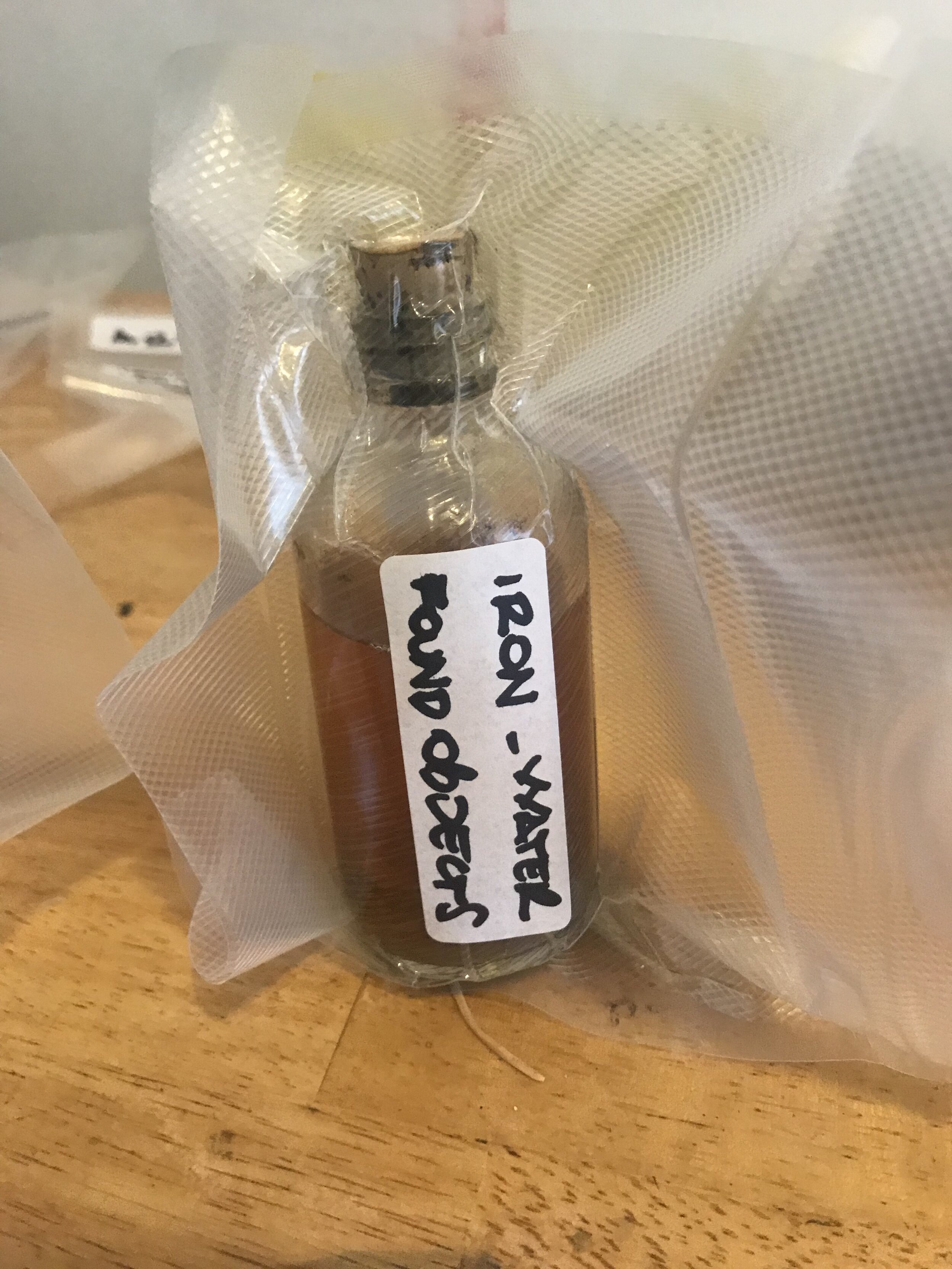

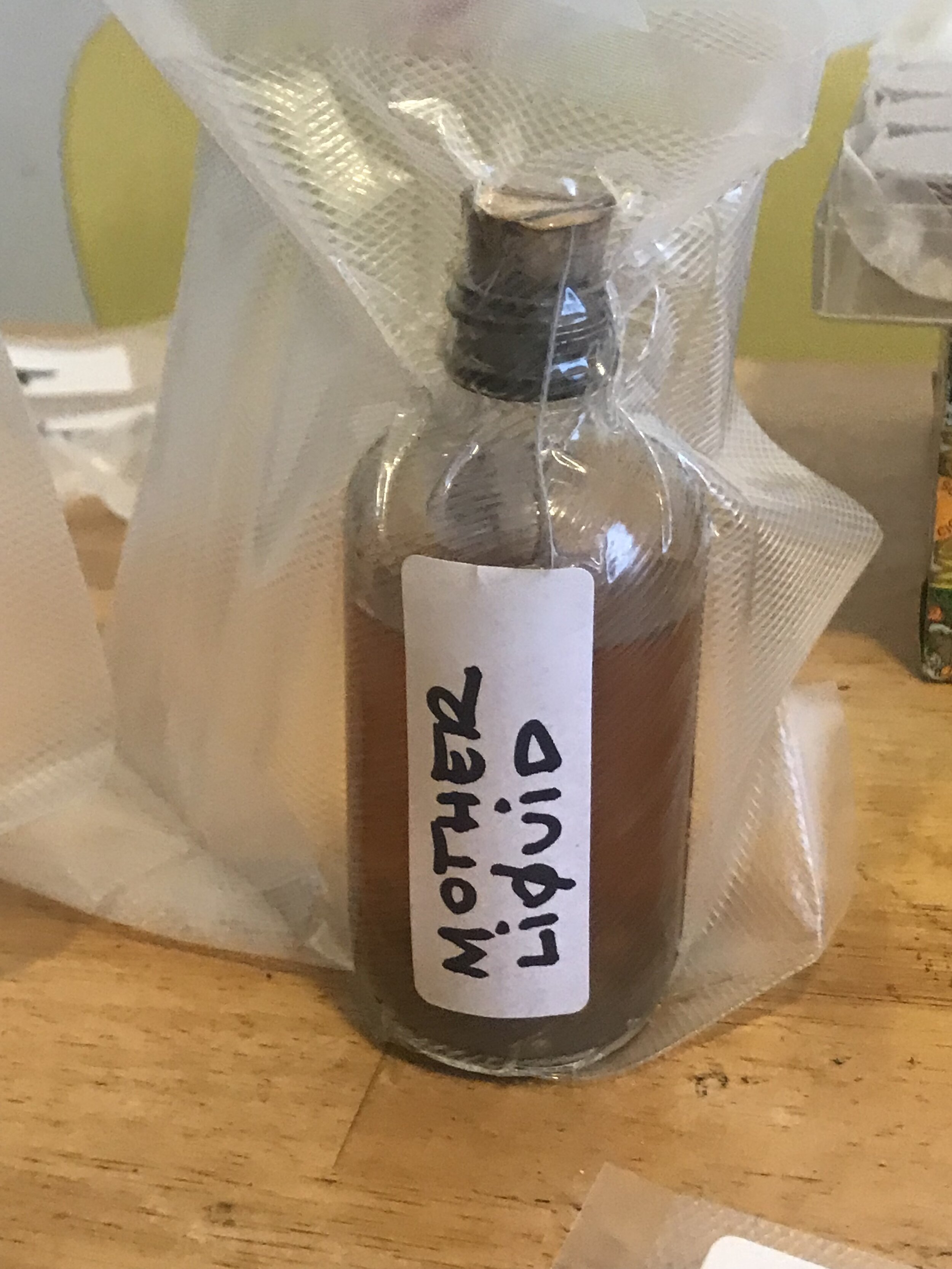

Working with Sporosarcina pasteurii as a collaborator emerged from this understanding. Rather than introducing life into the system, the bacteria became a way to work with processes already present in soil. Through studying biomineralization and observing calcium carbonate precipitation, I began to see bacterial activity as a connective tissue—binding matter, time, and scale, and revealing how form can emerge through cooperation rather than imposition.

Eggshells, Waste, and Circularity

Alongside soil, I chose to work with eggshells—discarded remnants of daily consumption that carry calcium already shaped by biological processes. Their inclusion reflects an understanding of waste not as residue, but as matter displaced from its cycle. Eggshells arrive with histories of formation, use, and disposal; reintroduced into the system, they participate once again in microbial activity. This choice aligns with an awareness of the microbial commons: a condition in which life-sustaining processes—decomposition, mineralization, and nutrient cycling—are collective and ongoing, moving across bodies, environments, and scales.

Thinking about making with what is already available, I became increasingly attentive to circular forms of material use. I began collecting eggshell waste from my kitchen, from friends’ kitchens, and eventually from a local bakery that generously donated larger quantities. Working with a matrix composed of 50% local soil and 50% local eggshell waste allowed me to remain within a logic of circularity—adding to the earth with materials already shaped by living systems, rather than extracting new ones.

Calcification as Process

Calcification unfolded slowly and required a different relationship to time. Working with S. pasteurii meant learning how to wait and how to attend to conditions rather than outcomes. Much of the process remained invisible for long stretches—hours, sometimes days—before any change could be perceived. Growth, activation, and mineral precipitation did not occur immediately; they accumulated quietly, often revealed only through subtle shifts in texture, coloration, and smell.

Culturing the bacteria demanded precision and care, but also flexibility. Protocols provided structure, yet they could not account for every variable. Decisions entered the process through observation and adjustment—how long to wait, when to intervene, when to let the system continue without interference. Calcification did not occur as a singular event but as a gradual negotiation between biological activity, material composition, and time.

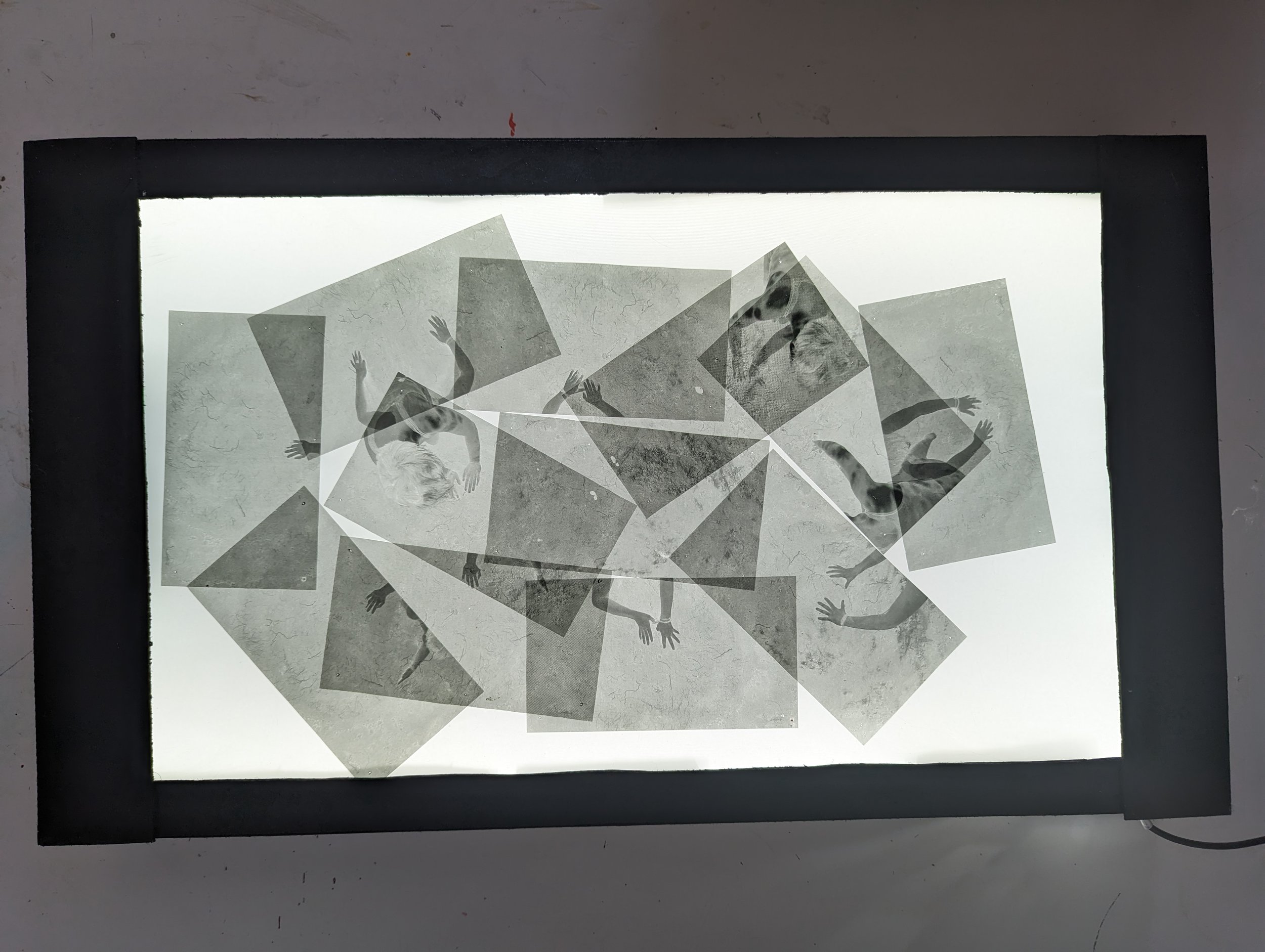

I worked to create conditions under which form could emerge. The bacterial metabolism—specifically its ability to precipitate calcium carbonate—acted as a binding agent, transforming loose aggregates into cohesive matter. What interested me was not control, but collaboration: allowing microbial activity to mediate relationships between soil, eggshell, moisture, and gravity. Calcification became a temporal process, one that required trust in unseen work taking place at scales beyond direct observation.

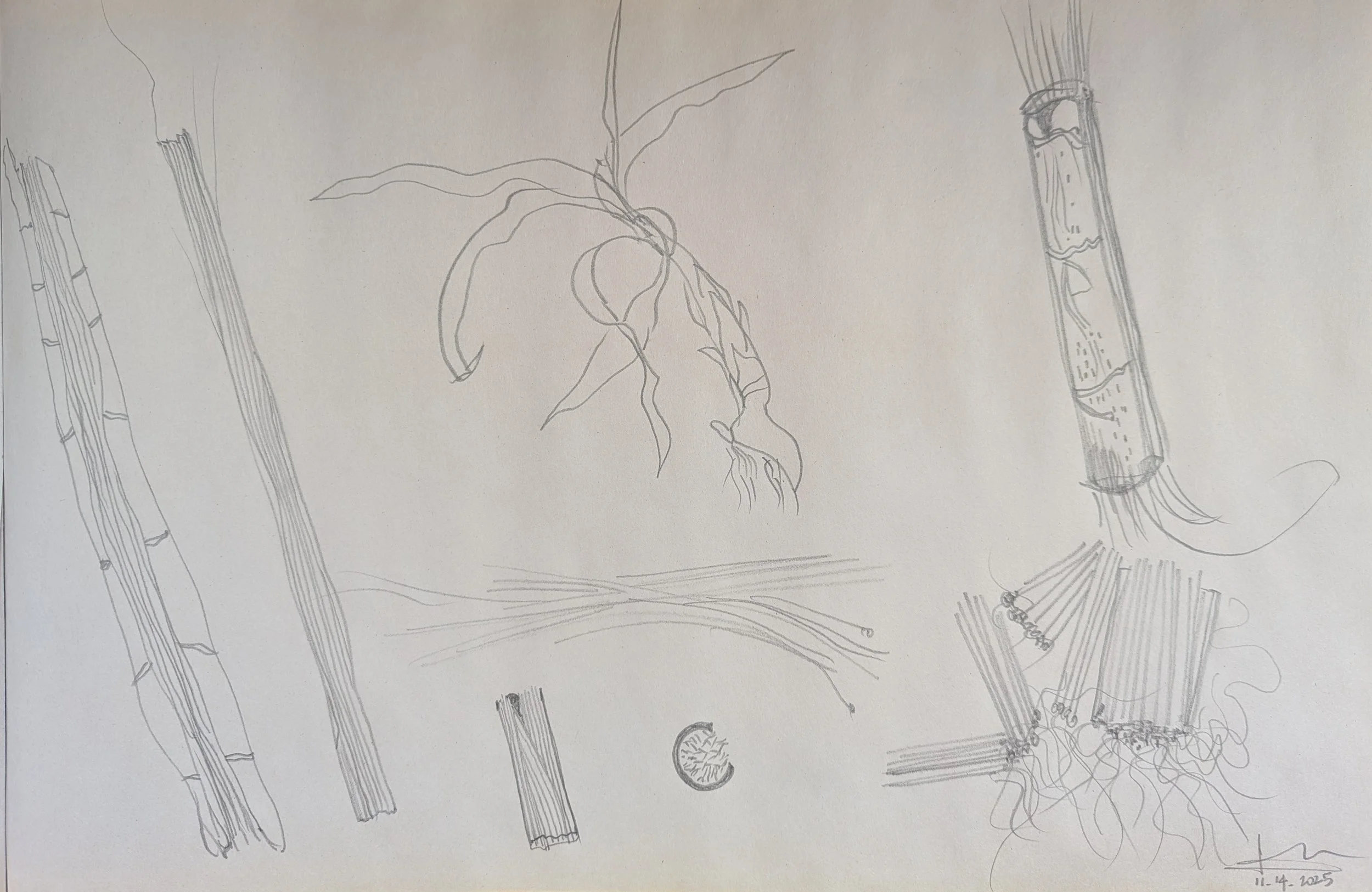

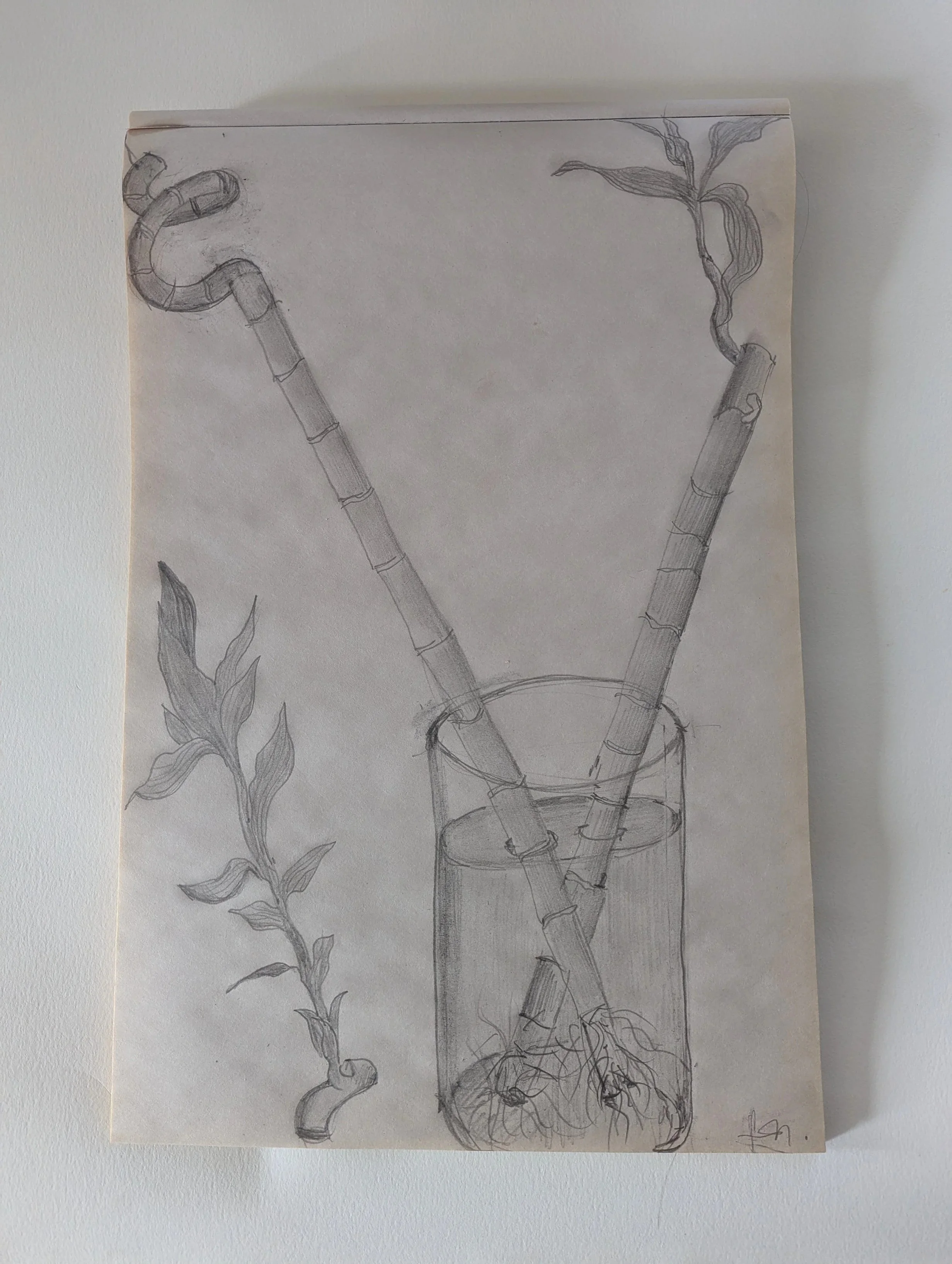

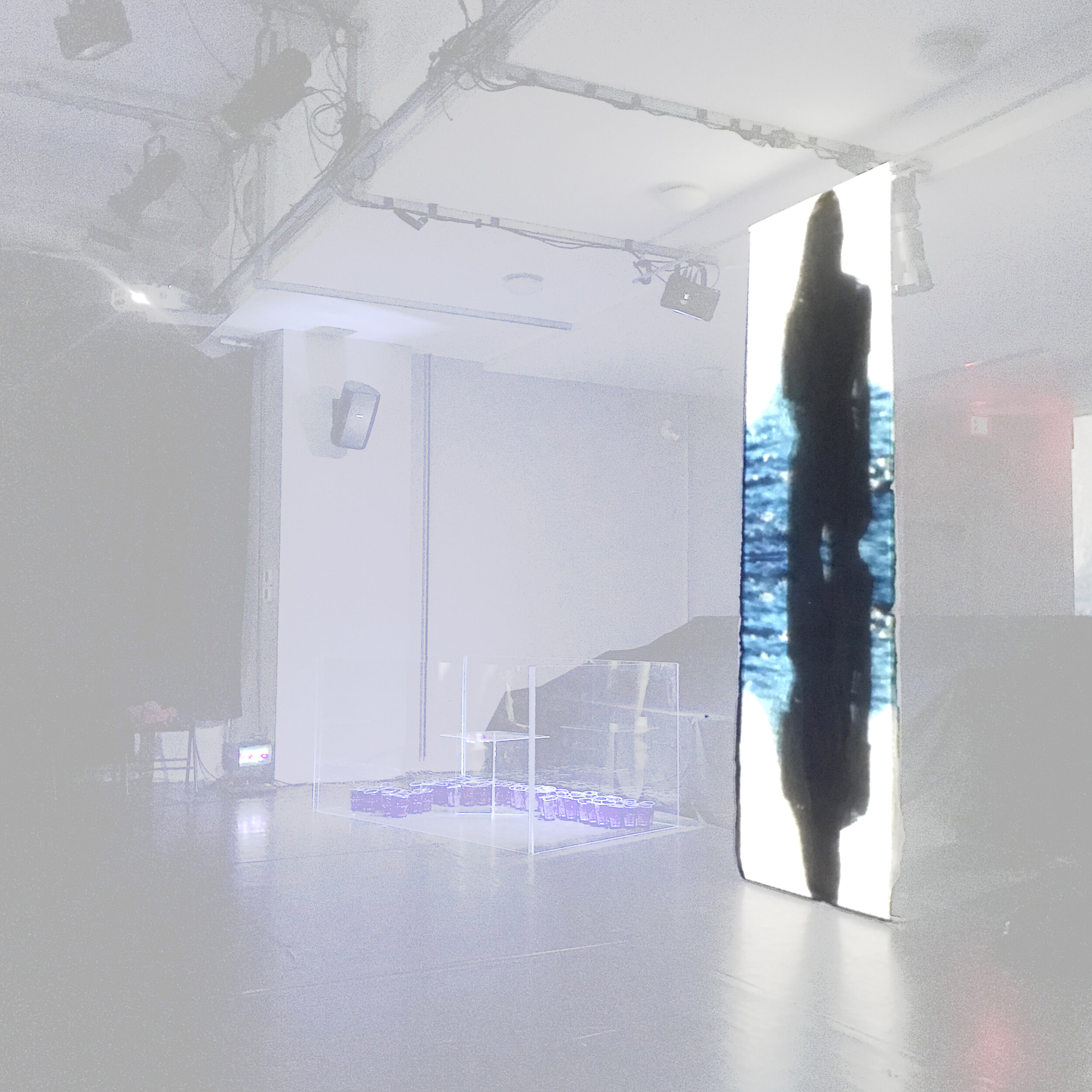

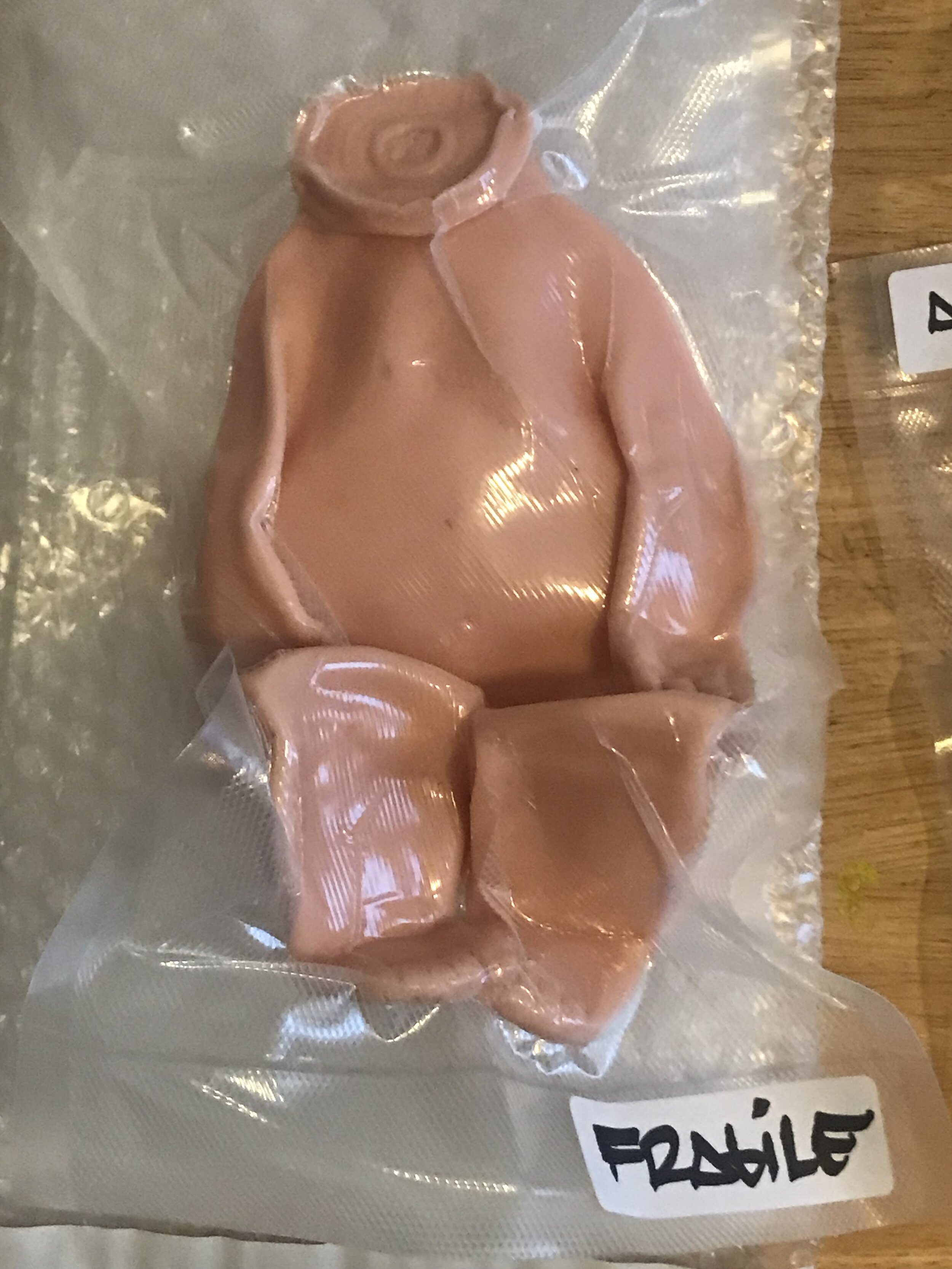

Form, Surface, and Crust

The forms that emerged from this process carry the traces of their making. Repetition played an important role—casting multiple samples allowed differences to surface: variations in density, coloration, texture, and cohesion. Surface became a primary site of attention. Rather than functioning as a finish, it accumulated slowly through mineral formation and microbial activity. I began to think of these surfaces not as skins, but as crusts—thickened layers formed through duration and interaction. A crust holds time. It records pressure, pause, and accumulation. Fragile, yet persistent, it remains.

Crust differs from skin in that it does not protect what lies beneath by separation, but by density. It is not applied; it forms. In these works, the surface acts as a threshold between visible form and invisible process, between what can be touched and what remains unseen. Cracks, fissures, and granular textures do not signal failure, but reveal how the material negotiated stress and transformation.

Together, the forms operate as a material archive of the process itself. They do not resolve the tension between fragility and stability; they hold it. What remains is the experiencing of a process—a sustained engagement with a living system.